Tommy Martin: The roaring Premier League juggernaut has survived it all

I LIKE THE KICKING: The famous Sky Sports Premier League ad from 1992.

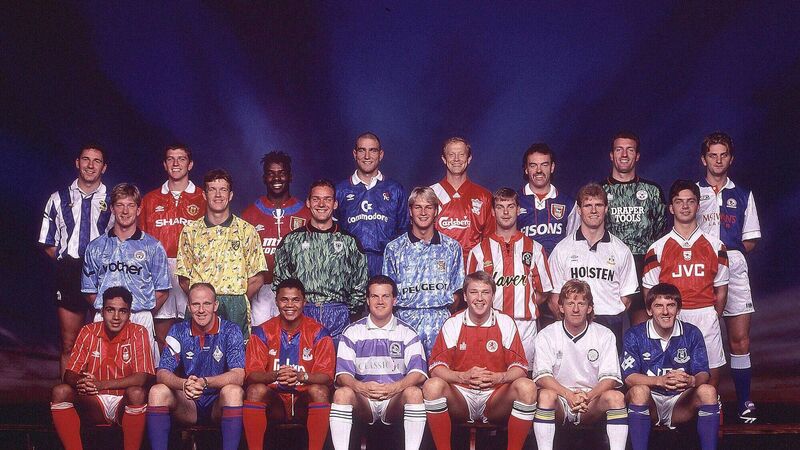

You might have seen the photo doing the rounds this week as the Premier League’s 30th season dawns. A promotional shot from around this time back in 1992/93, featuring one player from each of the 20 clubs competing in the inaugural chapter of English football’s brave new world.

There they were, the best and brightest of the English game: Andy Sinton, Gordons Durie and Strachan…er, Tim Flowers… (squints really hard) is that John Wark? Andy Ritchie is there representing Oldham Athletic, who’ve just dropped out of the Football League. There’s David Hirst of Sheffield Wednesday and Lee Hurst of Coventry City, two clubs once sturdy top-flight regulars since fallen on hard times.