Paul Rouse: When Kilkenny gained an extra man in an All-Ireland final parade

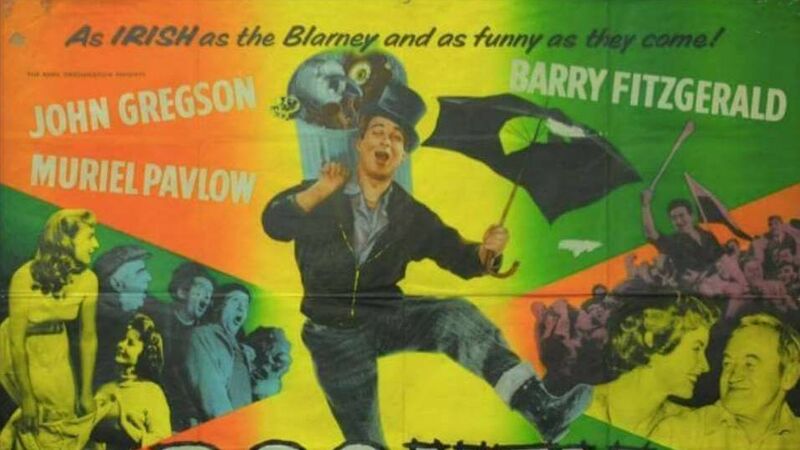

Rooney (1958), that features John Gregson, the man who walked in the parade with the Kilkenny team.

On 24 November 2008, Regina Fitzpatrick – a researcher with the GAA Oral History Project – travelled to Ferrybank in Co. Waterford and interviewed Paddy Buggy, former President of the GAA and former All-Ireland winning Kilkenny hurler.

It is an extraordinary interview, running over 4 hours and 12 minutes, Paddy Buggy – by then just about to turn 80 – gave a vivid insight into a lifetime lived in the GAA.