Eimear Ryan: Cody and Kiely couldn't be more different in style

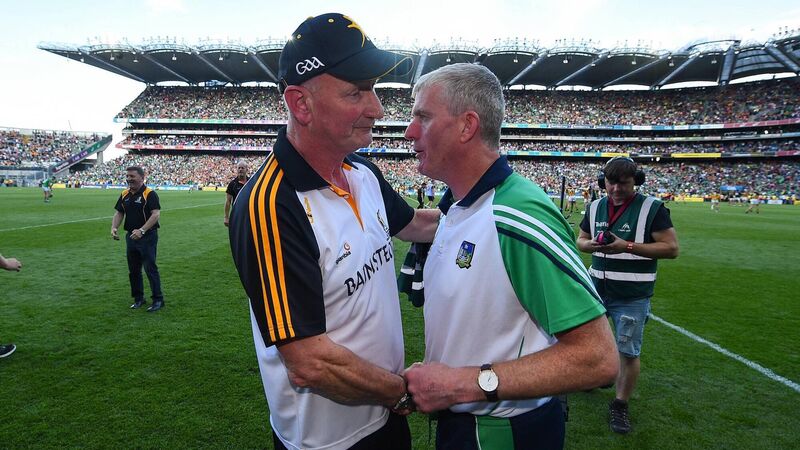

DIFFERENT BUT EFFECTIVE: Kilkenny manager Brian Cody and Limerick manager John Kiely shake hands. Pic: David Fitzgerald/Sportsfile

Your correspondent is in New York for the month of July, aka the business end of championship, and so has been relying on GAA Go for access to matches. It’s a pretty good service, with two fatal flaws: 1, it doesn’t include camogie; and 2, it’s expensive.

I bought a package including the All-Ireland semi-finals and final for $39, but last weekend’s Sunday Game wasn’t included, so I had to shell out $12 for the privilege. I regret nothing – you have to keep an eye on what The Lads are saying, and it was great to see Brendan Maher’s assured debut in what is hopefully a long career of punditry to come.