Paul Rouse: Lessons from sport lost on Putin - and Mick Wallace

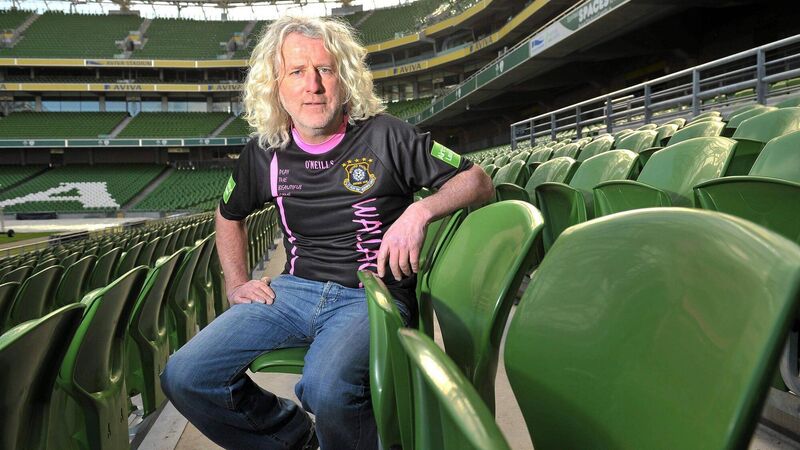

Mick Wallace, then Wexford Youths manager, pictured at the launch of the 2011 Airtricity League. The MEP voted against a European Parliament resolution which condemned the Russian invasion and demanded Putin immediately pull his troops out of Ukraine.

Everyone who loves sport has a personal story that explains this love. This is a story which is usually built into the sheer physical pleasure that comes from the act of playing.

For most people who love sport, the connection goes far beyond the physical. It is, instead, embedded in the meaning of their lives.