Eimear Ryan: When medals are worth more than their weight in gold

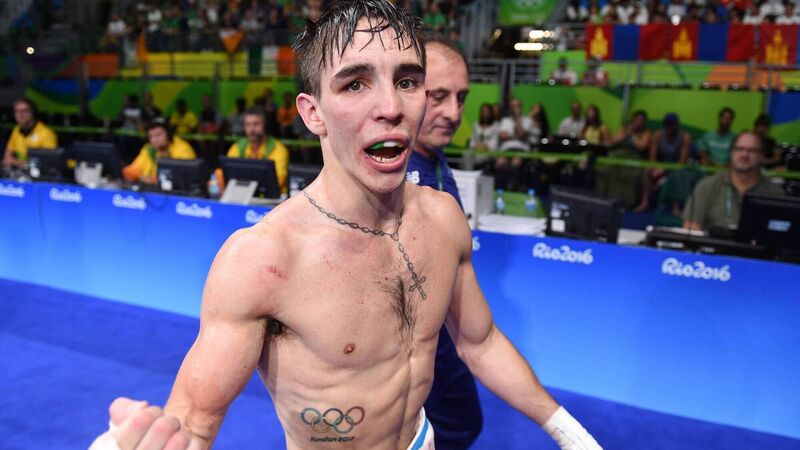

Michael Conlan of Ireland following his Bantamweight Quarter final defeat to Vladimir Nikitin of Russia. Picture: Stephen McCarthy/Sportsfile

It's the business end of the championship for clubs, that crunch time when the spoils are divvied up for another year. On nights out, whether celebratory in nature or more about drowning sorrows, players are reflecting: On where it went wrong or right, on standout scores, on turning points. On the season gone by and the season to come.