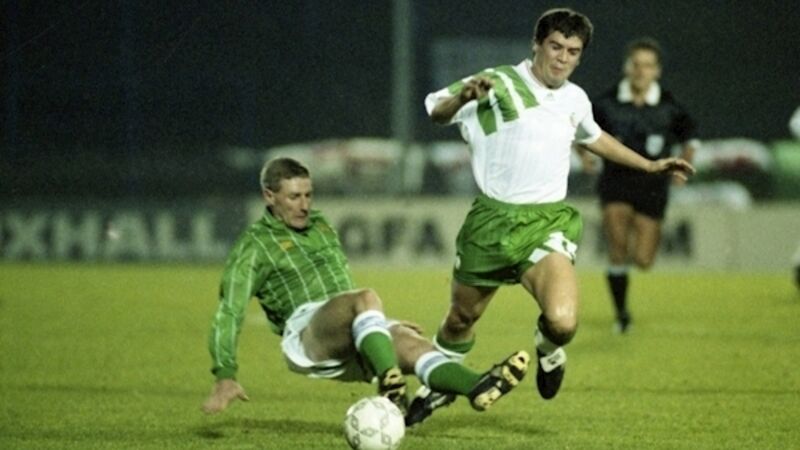

After bile of Windsor Park 1993, peace came ‘dropping slow’ for the North

The recent announcement of a joint FAI/IFA bid for the 2023 Uefa U21 Euros, to include stadia from Ballymena to Cork, is an example of the current good working relationship between the two associations.