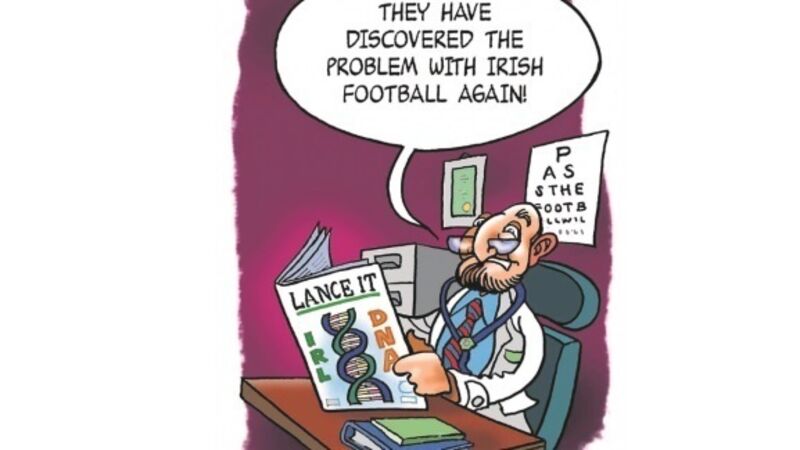

Why does every international break prompt morose introspection?

Perhaps it is to do with the break itself, something about this disruption in the natural rhythms of Premier League life that affords us this time and space for morose introspection.

Or maybe the lack of time and space we make for ourselves on the pitch during these grim fortnights is partly down to all the navel gazing — triggering an epidemic of existential crises whenever the ball is at our feet.