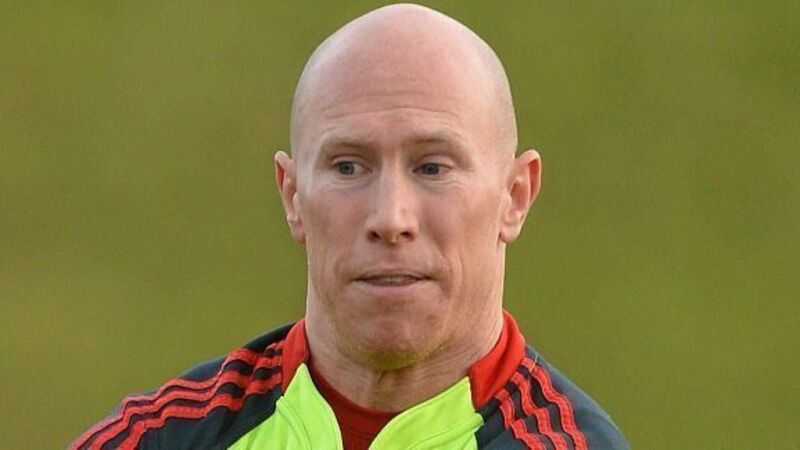

Lionhearted Legend - Interview with Peter Stringer

It’s 15 years ago this very month that he broke into the Irish team and the Irish public imagination along with it: Italy’s first Six Nations was his first, too.

Any of us around at that time has the image etched forever in the mind: himself and O’Gara either side of Papa Gaillimh for the national anthem with three other debutants — Shane Horgan, Bull Hayes and Simon Easterby — elsewhere along the line. That first day out — and win — against Scotland, the nerves and occasion got to a couple of them; O’Gara in his autobiography would talk about how for the next day against the Italians he and Stringer came up with different calls to buy him some more time at that level. It was ‘10’ if he was kicking, ‘Chilli’ if he was running.