Paul Rouse: Striking the right note - Why songs are an integral part of GAA culture

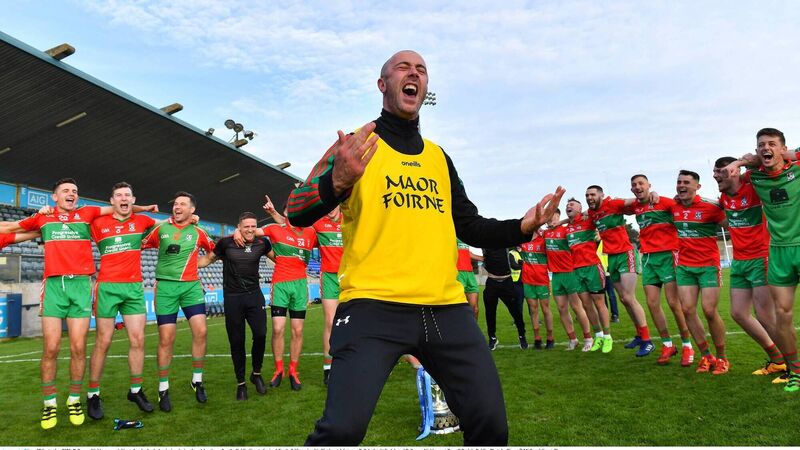

FINDING THEIR VOICE: Ballymun Kickhams coach Simon Lawlor leads the singing as they celebrate their Dublin SFC final win over Ballyboden St Enda’s last September. County songs played after matches in Croke Park are not about sport and, indeed, do not even reference sport. Instead, they relate to place.

There’s a thing that happens in Croke Park on big-match day that stirs the emotions like nothing else.

After the full-time whistle, the way a song associated with a particular county fills the air from the tannoy system brings together music and sport in a transcendent way.