Paul Rouse: Be it Croke Park or Camp Nou, home advantage counts

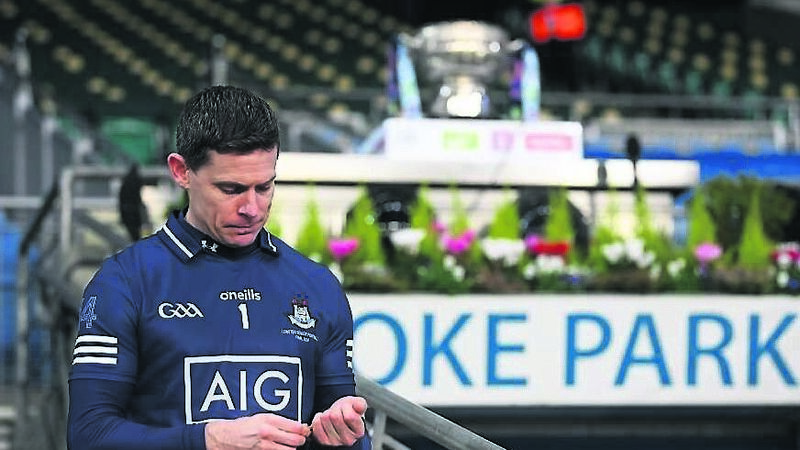

Dublin captain Stephen Cluxton after lifiting the Delaney Cup following the Leinster final win over Meath last month. Picture: Stephen McCarthy/Sportsfile

The manner in which Dublin dismantled Meath was so absolute that a tipping-point has been reached.

Meath are the second-best team in Leinster. They have made good progress under Andy McEntee to the point where there was a general sense that they had closed the gap on Dublin.