Timeless design partnership of Charles and Ray Eames

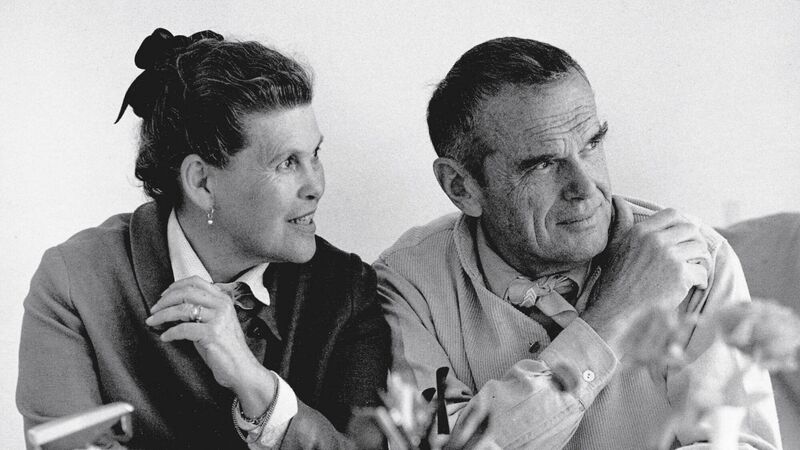

Charles and Ray Eames in the 1970s. Picture: vitra.com

Bobbing on a battered aluminium group chair that collides rudely with this knee-hole desk, I’m heady just writing about the romance and creative expressions of Charles and Ray Eames. As my teen puts it while perusing a photograph of the pair — “relationship goals”.