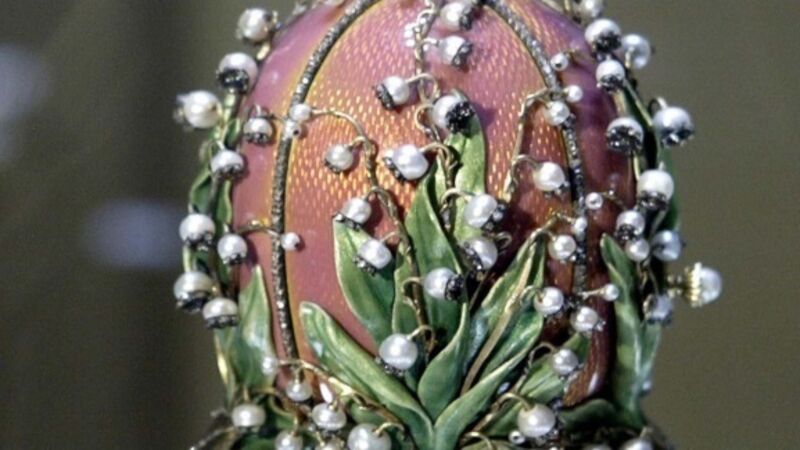

Vintage View: Cracking open a very special Easter egg

looks at some very special eggs for Easter — those of Carl Fabergé.

Eggs have been a sacred symbol and favourite device in the arts for millennia.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEKya deLongchamps looks at some very special eggs for Easter — those of Carl Fabergé.

Eggs have been a sacred symbol and favourite device in the arts for millennia.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Newsletter

Sign up for our weekly update on residential property and planning news as well the latest trends in homes and gardens.

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Friday, February 13, 2026 - 11:00 AM

Friday, February 13, 2026 - 11:00 AM

Thursday, February 12, 2026 - 5:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited