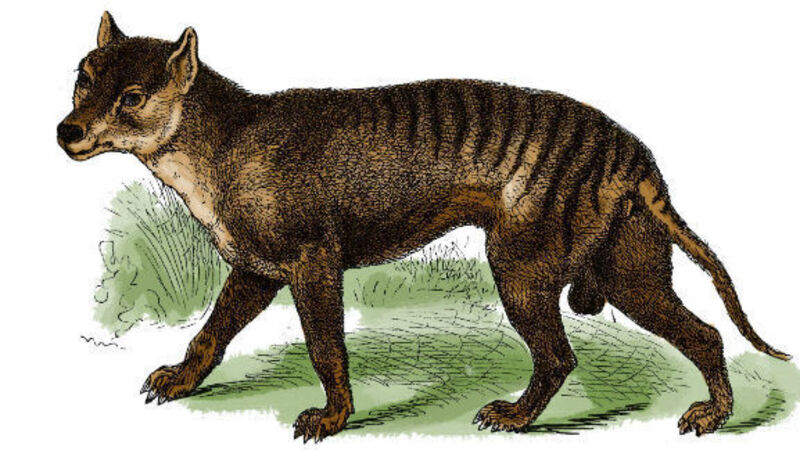

Tasmanian Tiger in line of sight

he National Museum’s Mammals of the World exhibit includes a dog-like creature from Australia known as the ‘thylacine’. It’s not a specimen of which the museum should be especially proud.

When curator Roberst Scharff attended a conference in Australia in 1914, he committed what would nowadays be considered an unforgivable wildlife offence. Dublin already had a skeleton of the critically-endangered mammal; a specimen ‘obtained’, ie shot, in 1884. Skulls, dating to 1889, were also in the collection but Scharff wanted to acquire a better example of this rapidly disappearing species. A hunter was asked to find and kill a thylacine, the skin and bones of which were shipped to Dublin for mounting.