Vintage View: The history of glazing and other specialist finishes

Last week, we took a look at the body of a ceramic, the material, or paste from which it’s made.

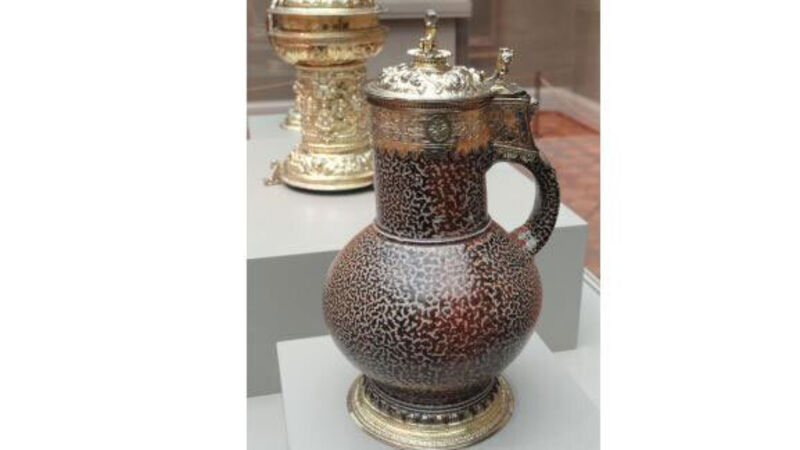

Now most bodies (with the exception of tough but gorgeous old porcelain), are to some extent porous, and to render them watertight and to further beautify them, a top glaze was added, often to the outside and inside, but sometimes to the inside alone.