Irish Examiner view: Tech will not pause for us to catch up

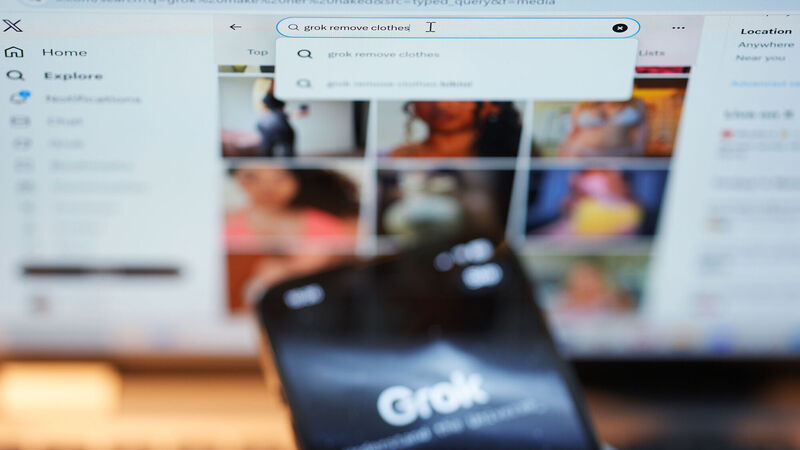

The coverage of AI 'nudification', particularly on platforms such as Grok, which has been misused to generate non-consensual sexualised images of women and children, has jolted public consciousness and policymakers alike. Picture: Yui Mok/PA