Timoleague and Quin abbeys could be Ireland's Carcassonne

The medieval city of Carcassonne in France was restored by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Ireland should emulate his work on landmarks including Timoleague Abbey in Cork and Quin Abbey in Clare. Picture: iStock

You cannot truly say you have been to Ireland until you have driven into the village of Quin, County Clare, on the road that travels west from Scarriff.

Rounding a bend, you catch your first glimpse of the wonderful abbey with its slender tower rising from a sturdy limestone base. The people of West Cork might argue that the approach to Timoleague is even more striking than the approach to Quin. And then, of course, there’s Cashel…

These medieval ruins — whether abbeys, monasteries, or friaries — found on the outskirts of villages and towns across Ireland, with their pointed arches and their lancet windows, are breathtaking when glimpsed from the comfort of a car.

Up close, however, the perspective shifts. When you realise the church has no roof and the entrance to the cloister is obstructed by metal barriers, the poetic beauty of the monastic ruin suddenly fades.

HISTORY HUB

If you are interested in this article then no doubt you will enjoy exploring the various history collections and content in our history hub. Check it out HERE and happy reading

Most of our monasteries and friaries were built after the 12th-century Norman invasion, a period when Ireland joined what could be described as a medieval version of the European Union.

Their prominence in the landscape gives us a direct insight into how Ireland became integrated into European Christendom.

It also helps us to understand how our island came to be settled in a manner that still resonates to this day.

The abbeys flourished for centuries. The beginning of their end can be traced to a single, transformative event — the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII.

Henry’s famous break with Rome led him to suppress Catholic monastic houses not just in Ireland, but in Britain as well.

Some of our abbeys survived his initial attempts to crush them, and indeed, there is evidence that a vestige of religious activity continued in places like Quin until the 19th century.

Nevertheless, the legal and financial structures that supported these buildings were either sharply severed or severely throttled. Time and the elements eventually finished what Henry began. A slow and sad decline was inevitable.

However, the way in which these medieval buildings appear to us today is not entirely the result of their slow demise. It involves a conscious approach that we, as a society, have adopted regarding how buildings should be conserved.

In Ireland, we tend to maintain our very old buildings in the state in which we find them. We generally do the least work necessary to ensure they remain standing, focusing on maintaining original fabric rather than re-establishing discontinued uses.

The wider debate over how societies should go about conserving structures of value has its beginnings in Roman times. We need not go back quite that far; we can pick the argument up in the 19th century with the clash of philosophies between two giants of architectural thought.

The first, an Englishman named John Ruskin — a strange character, famously married to Effie Gray — argued that we must “watch an old building with an anxious care” rather than attempt to restore what has been lost.

Simplifying his ideas a little, he suggested it was better to let a building die with dignity than to create a “false history” through rebuilding.

To Ruskin, restoration was “the most total destruction which a building can suffer”.

He was also deeply taken with ruins and, in this regard, his view is related to the ideas of the Romantic movement that was then gaining momentum across Europe.

For the Romantics, the roofless abbey covered in ivy proved the inspiration for many a painting and a poem.

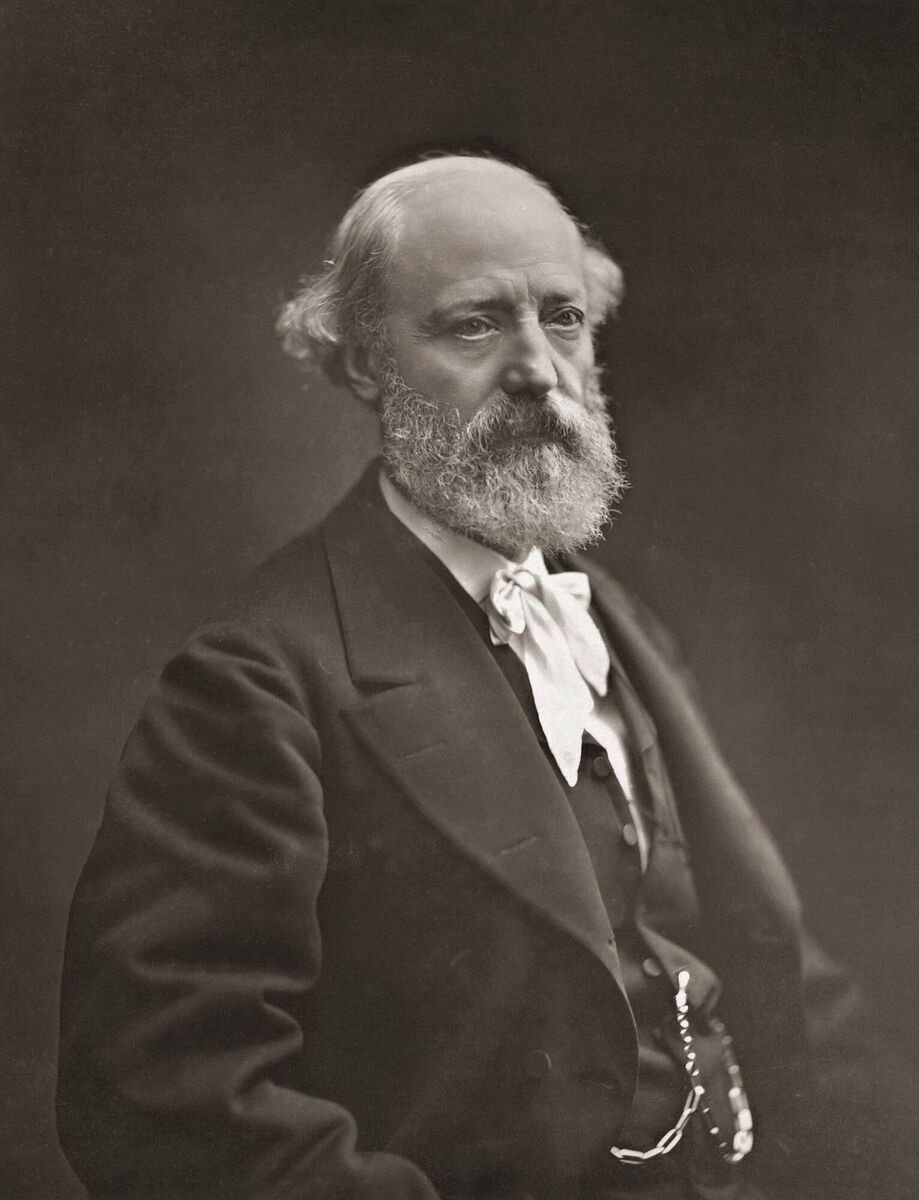

Ruskin’s opponent was the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

He defined restoration as “re-establishing [an edifice] in a complete state that may never have existed at any given moment”. Instead of preserving crumbling walls as empty voids, he rebuilt them.

He famously restored the walled city of Carcassonne and designed the iconic spire of Notre-Dame de Paris.

While his work offends conservation purists, he did create some of the most visited and culturally vibrant sites in Europe.

In Ireland, we have generally taken the Ruskinian line in conservation and, as a consequence, our fields are dotted with medieval ruins.

But the question must be asked: Have we ever seriously interrogated why we do this?

It really is worth considering if preserving the ruin of a monastery is always the best option available to us.

By maintaining them only as shells, we preserve a sense of “poetic decay” but lose a most important element of culture — continuity.

We treat these buildings as if their story ended the moment the roof fell in, rather than allowing them to evolve along with us as part of a living present.

We have, on occasion, strayed from Ruskin’s 'leave things as they stand' approach.

Holycross Abbey in Tipperary was restored to a living place of worship in the 1970s.

While some in the conservation community were unconvinced by the experiment, the abbey’s existence does present us with a compelling alternative to the ruin.

The abbey at Holycross provides an undeniable service to its community. It also allows architecture to do what it was designed to do — enclose space for human activity.

So, imagine if Quin or Timoleague were re-roofed and their interiors returned to community use? At both locations, much of the original fabric remains standing, so figuring out the original arrangements would not require a great deal of speculation.

The counterarguments to restoration are well rehearsed and often valid.

First, there is the matter of cost: In Ireland, we frequently struggle to deliver public projects at a reasonable price. It is not hard to see how the restoration of even a modest monastic structure could end up costing the price of a small hospital.

Furthermore, it is not enough to simply find a use to justify the restoration of a monastery; we would need firm assurances that any new use would sustain itself for a reasonable period.

However, a thoughtful restoration would confer one critical advantage: It would give us all access to an unusual and genuine cultural experience. That is, a chance to understand something fundamental about the medieval abbey — a chance to come closer to what medieval Christianity and community life were about, even if we do not experience it in its fullest religious sense.

When it comes to medieval structures, our traditional approach to conservation has, perhaps, been a little too narrow. We have preserved the ‘authentic’ ruin, yet as we stand in the roofless choir of Quin Abbey and gaze up at the grey sky, we must ask ourselves: Are we truly engaging with our culture, or just a 19th-century Victorian idea of what our culture should look like?

There is no single correct answer, but the conversation is overdue for a dusting off. Perhaps we could move past the dogma of the ruin and initiate one or two pilot projects with robust plans for reuse.

If the worst possible outcome is that we create a few more versions of Holycross Abbey, then we really have very little to fear.

- Garry Miley is a lecturer at South East Technological University’s Department of Architecture