'Experts' must stay in their lane

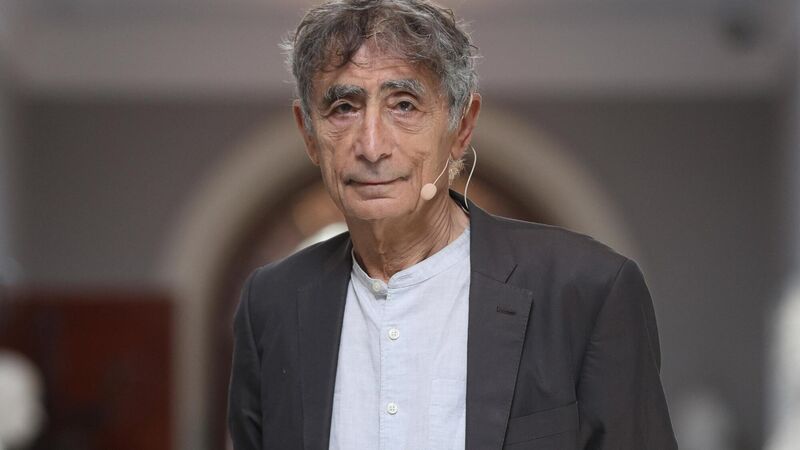

In the area of childhood and trauma studies, Dr Gabor Maté is revered by millions. File photo: Sasko Lazarov / Photocall Ireland

I love to cook. My passion for cooking was ignited by my first husband’s mother when I was just 20 and living in Singapore. She was an incredible cook, and I learnt a lot from her. You can be sure I know my spices and how to choose fresh fruit and vegetables like a boss.

I also know quite a bit about cooking delicious, nutritious, meals on a (very) tight budget, and am always happy to pass my knowledge on. If you came to my home, I would be delighted to offer you dishes that I hope will make your mouth and tummy happy, and make you feel cherished.