Catherine Conlon: Joe Wicks's Killer Bar has achieved what no stuffy science report can do

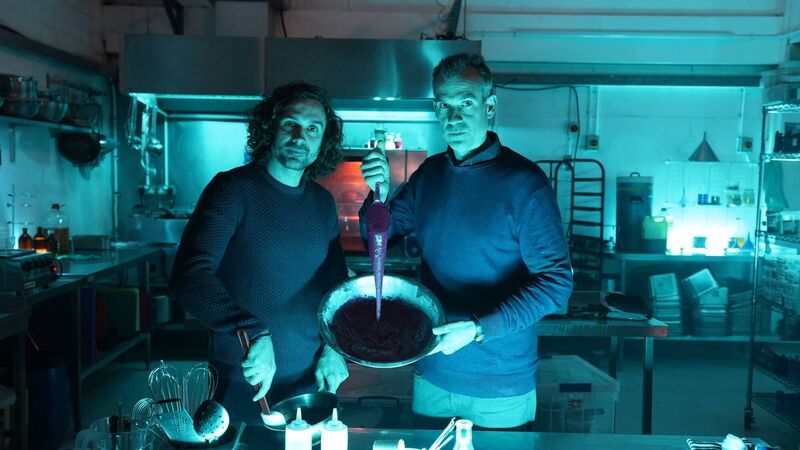

Joe Wicks and Chris van Tulleken have developed a protein bar deliberately designed to be the 'worst possible' bar that can still legally be described as offering health benefits. Picture: KEO Films

Influencer Joe Wicks has caused a furore among nutritionists by carrying out a highly provocative stunt that he designed to convince the British government to change food laws for good.

He and Chris van Tullekan, author of Ultra-Processed People, have developed a protein bar deliberately designed to be the "worst possible" bar that can still legally be described as offering health benefits.