Authoritarian states have powerful reach — even in Ireland

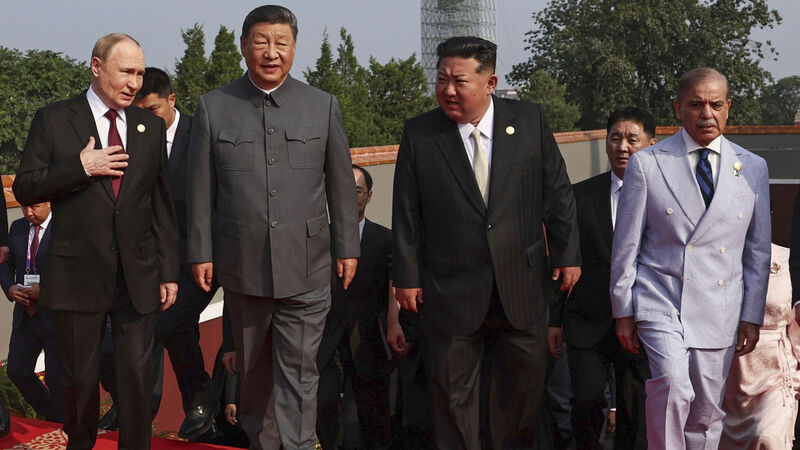

From left, Russian president Vladimir Putin, Chinese president Xi Jinping, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and Pakistani prime minister Shehbaz Sharif arrive at a military parade to commemorate the 80th anniversary of Japan's World War II surrender held in front of Tiananmen Gate in Beijing, China, last month. Picture: Alexander Kazakov, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP

Last month, China’s Xi Jinping, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un captured the global spotlight by appearing together in Beijing for a military parade.

None of them has ever won a fair and competitive election, permitted a free press to investigate the policies or practices of them or their governments, and or allowed political opponents to question, let alone challenge, their political rule.