Is Trinity College right to fear plans for greater oversight?

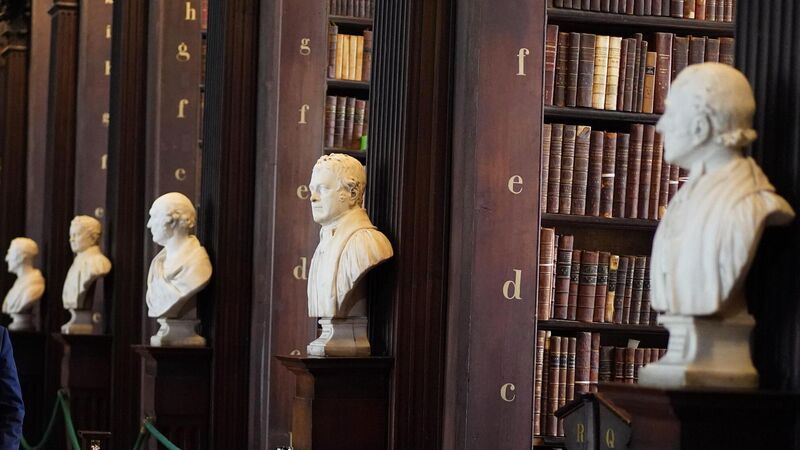

The Long Room in Trinity College. Trinity has sought exclusion from the upcoming legislation on grounds that the reforms could threaten its autonomy and independence.

The first duty of a university is to teach wisdom, not trade; character, not technicalities, so wrote Winston Churchill. There is a value to universities that exceeds their ability to transfer specific skills and stimulate economic growth.

As reported by Daniel McConnell in this paper recently, a new Higher Education Authority Bill 2022 working its way through the Oireachtas which plans to reform university governance represents the greatest overhaul of how colleges are governed since 1971. The new bill which will make universities more accountable to the state is ruffling some academic feathers.