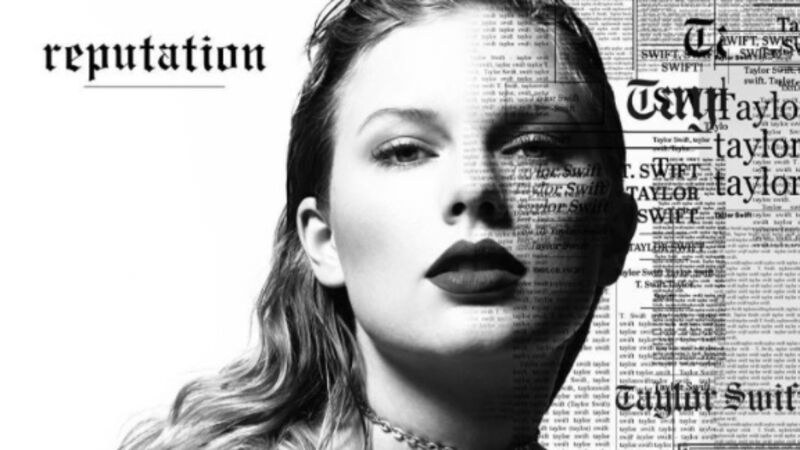

The media’s gaze can be difficult for celebrities to shake off

If you live your professional life in the spotlight than you can’t expect to set limits on the public’s curiosity or appetite for gossip, whether salacious or not, writes

In a recent interview with the Guardian, Mariah Carey said: “There is a price to pay for having a public life.”