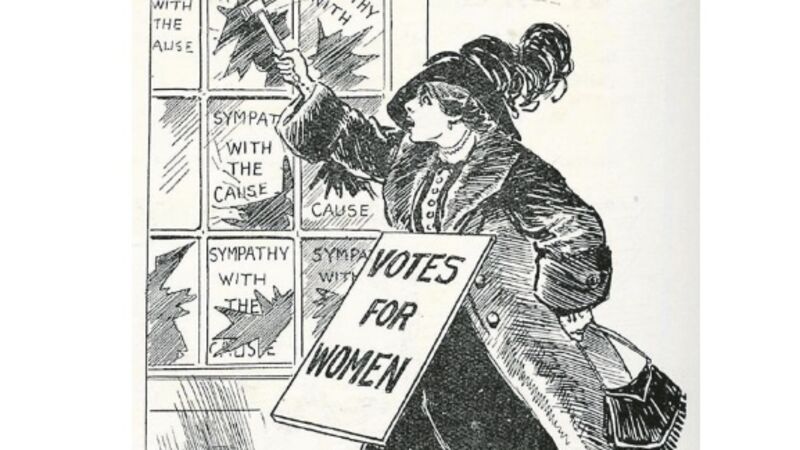

Creating a meaningful space for women’s voices to be heard

The difficulties inherent in commemorating the granting of votes for women must be confronted and not elided, says

Ireland is now in the throes of the decade of commemorations. A process of collective remembering and reflecting on the tumultuous events that led to the foundation and establishment of the Irish State has ignited public debate and new academic scholarship on the revolutionary period.