Political will can make the lives of children better but lots of work needs to be done

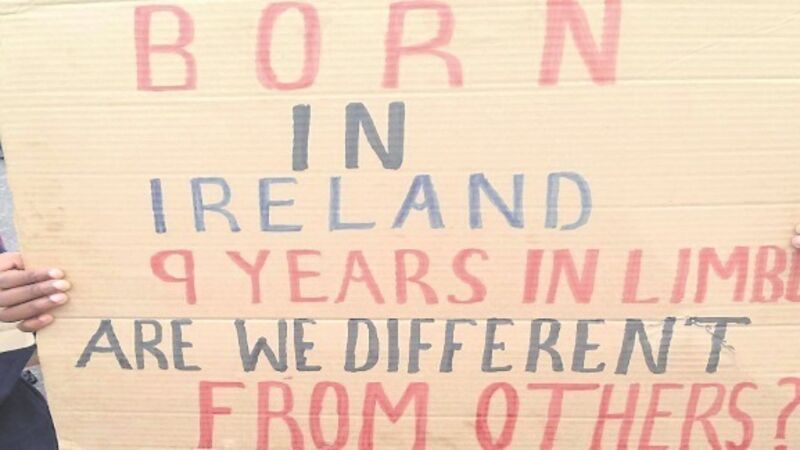

TODAY, I am in Geneva to witness a top UN body put a spotlight on Ireland’s treatment of children.

It’s the first time the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has scrutinised us in 10 years, so it’s a landmark day.