Why some thought it permissible to perpetrate the Paris attacks in God’s name

IN HIS 1990 book God and the Gun, Martin Dillon — who worked for the BBC in Northern Ireland for 18 years — tells of an encounter with a UDR man in the 1970s, during “the Troubles”, who admitted that he once “advocated beheading Catholics and impaling their heads on railings in the Protestant Shankhill area of Belfast”, telling his terrorist boss it was the “best means of terrorising the IRA”.

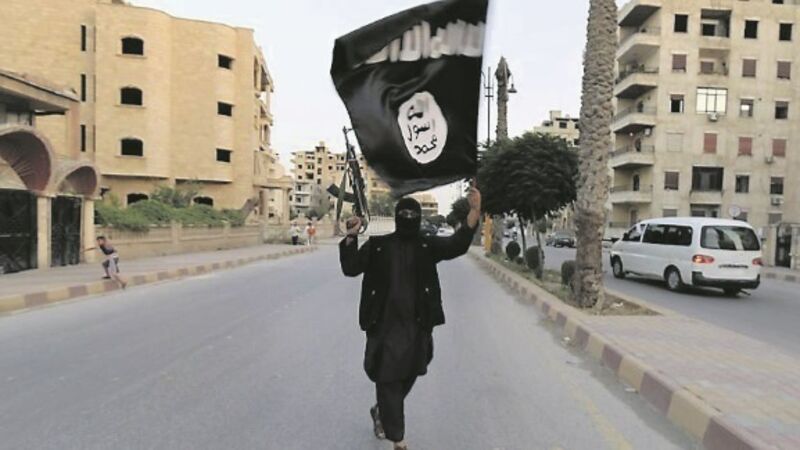

To a generation of readers brought up with headlines and news bulletins dominated by stories of beheadings, crucifixions, and mass rapes by jihadists associated with Islamic State (IS) in the Middle East, there will be something horribly and sickeningly familiar with this story from our own backyard here in Ireland.