Paul Hosford: Ireland must rethink its dependence on the US under Donald Trump

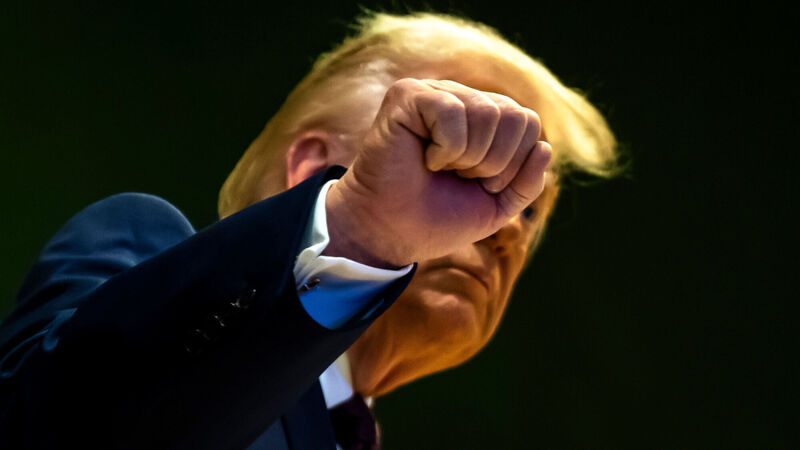

US president Donald Trump at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Trump had spent much of the preceding week ratcheting up his insistence that his country ‘needs’ Greenland. Picture: Laurent Gillieron/Keystone via AP

There were words.

Revoiced

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.