Clodagh Finn: Remembering the artist who illustrated Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

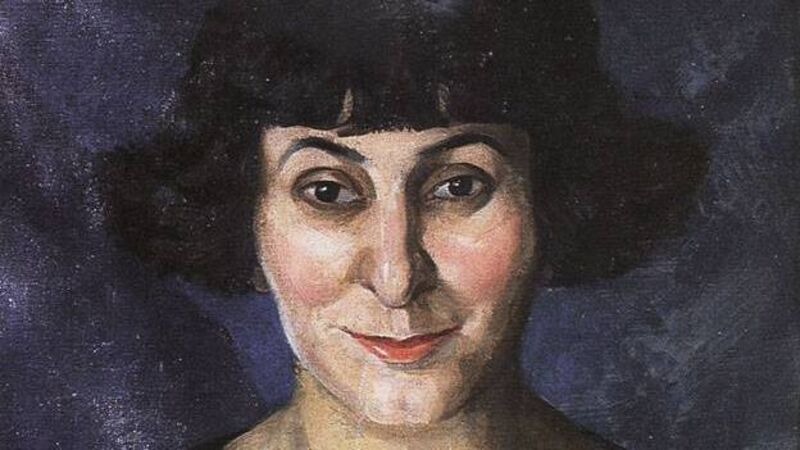

Stella Steyn had an exceptional career as an artist.

If there is one potentially unifying thing that has emerged from the controversy over the denaming (or not) of Herzog Park, it is the unexpected but happy return of artist Estella Solomons to the spotlight.

Her name has been mentioned several times in recent days in a pretty uncomfortable discussion about who in the Irish Jewish community deserves to be remembered or not.