Paul Hosford: Let's use the number of spoilt votes in Áras election to overhaul our entire political system

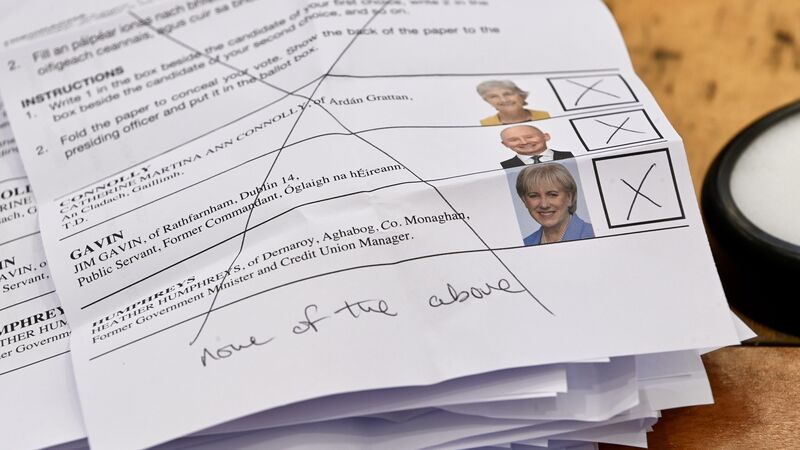

It would be foolish to suggest the 213,000 who spoiled their votes were all members of one homogenous movement. Picture: Larry Cummins

The decision of more than 213,000 people to spoil their votes in last week's presidential election has prompted considerable soul-searching.

In the media and on social media, mostly, where commentators grapple with what the vote means. Proponents of the mass spoiling campaign claim it as a shockwave to the Irish political establishment, but at the same time play down the landslide victory of Catherine Connolly.