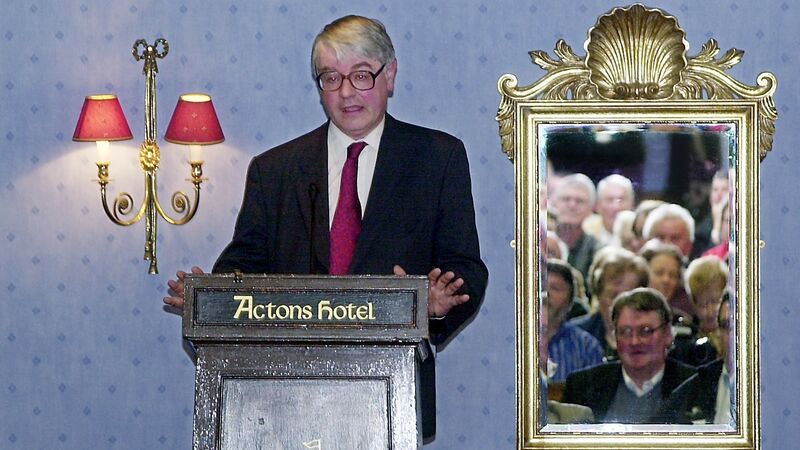

Fergus Finlay: Martin Mansergh was top of the list of peacemakers in the North

When the history of Ireland is written, and the scroll of Ireland’s peacemakers is settled, Martin Mansergh will be high on any list. Picture: Denis Minihane

The most unlikely Fianna Fáiler in the long and illustrious history of that party died last week. And he will, and should, have an honoured place in the history of his country — as well as his party — as a principal architect of a successful peace strategy.

Martin Mansergh was a shy man, never comfortable in the public arena. He was deeply intellectual, and carried himself with the air of an eccentric professor. He was always in the same rumpled grey suit, always with a laugh that could shatter glass.