On the death of Charles Haughey in June 2006, his protégé and successor as Taoiseach Bertie Ahern said of the man he called ‘boss’: “Charles Haughey made a huge impact on Irish life over a 35-year political career. I have no doubt [history’s] ultimate judgement on Mr Haughey will be a positive one.”

Inherent in Ahern’s comments of Haughey was the fact that many saw Haughey’s influence on Irish political life as a largely malign one, a corrosive one.

He became the epitome of largesse, corruption, avarice, and hypocrisy which stained Irish politics during that time.

The subsequent generation of tribunals that would cement Haughey’s legacy were to many a fitting epitaph for those who played fast and loose with the reins of power.

Various people have since his departure from high office sought to give their assessment of Haughey’s enduring legacy, and very few have ever sought to agree with Ahern’s prediction.

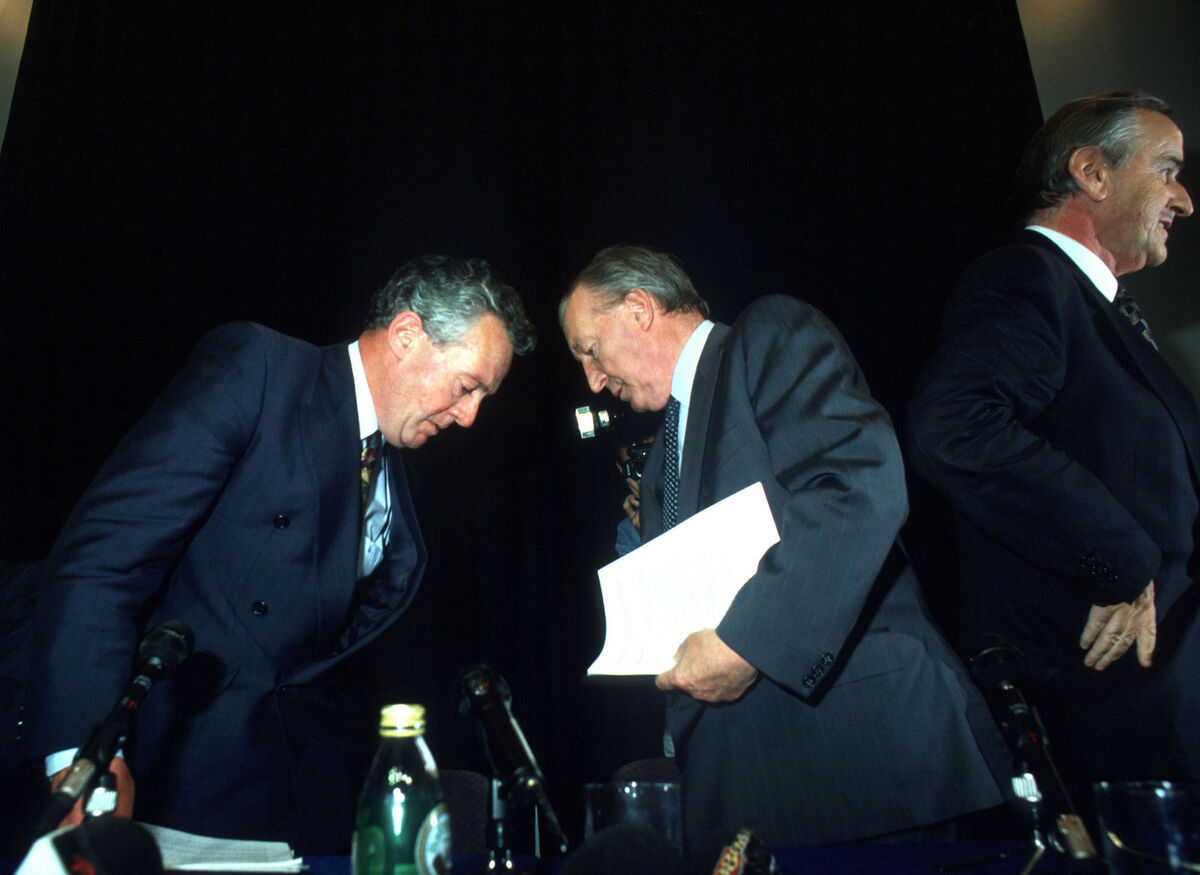

Des O’Malley, the founding father of the Progressive Democrats and Haughey’s primary nemesis in the 1980s, said he cast a “long dark shadow” over Irish political life.

Speaking during a 1999 Dáil debate, O’Malley chided the likes of Padraig Flynn and called on TDs to respond with courage to eradicate the “cancer of corruption” which fostered under Haughey’s tenure.

At a political conference in University College Cork held around the same time to assess the Haughey years, Fintan O’Toole, the Irish Times columnist said the hypocrisy evident in the gap between Haughey’s patriotic rhetoric and his unprincipled practice strengthens the notion that he merely used ideology as a convenient cover for self-enrichment, and the damage he continues to do to Fianna Fáil seems to underline the long-held belief that his divisiveness was a disaster for his party.

At the same event, then Sunday Tribune political editor Stephen Collins said Haughey’s hold over his party was based on fear and intimidation and that people were terrified of his wrath.

He managed to retain a hold over the party because of the fanatical support he enjoyed within the parliamentary party, the Fianna Fáil organisation, the media and the general public, Collins said.

On his death in 2006, historian T Ryle Dwyer concluded that Haughey was revered and reviled, loved and loathed.

“He leaves behind many positive accomplishments and dreadful failings,” Dwyer wrote.

On the release of former Fianna Fáil minister Conor Lenihan’s book on Haughey in 2016, Dwyer in the Irish Examiner drew a harsher conclusion by saying that Haughey did “real damage” as a result of his “poisonous legacy”.

Such harsh views have helped create an almost cartoonish myth around Haughey.

Those who supported him often painted him as the victim of a media witch hunt.

At his funeral, his youngest son Sean said the ordinary people on the street had a far better understanding of his father than his media critics.

The public generally always had “a much more balanced view” of his father than his opponents, he said. “It would seem everybody hates Charlie Haughey, except the people,” he quoted his mother Maureen as saying on one occasion after the former Taoiseach’s travels through the country.

As we now approach the 30th anniversary of Haughey’s downfall and resignation as Taoiseach in early 1992, that full reassessment of the career and life of the most controversial politician in modern Irish history is now due.

While an offering from veteran journalist Vincent Browne has long been awaited, it is a 700-page ‘cradle to grave’ effort from Dublin City University Law Professor Gary Murphy, due for publication next week, which first seeks to address that issue of Haughey’s legacy in a truly historical as opposed to a contemporary context.

With exclusive access to the Haughey personal papers, Murphy is clearly seeking to offer a more balanced review of the life and times of Haughey.

Was he saint or sinner?

Was he neither? Was he both?

Described by many, including Charlie McCreevy, as the most talented and influential politician of his generation, Haughey’s undoubted successes in public life have been long overshadowed by the many scandals and corruptions he engaged in.

While accepting that any anthology as donated by the Haughey family is not a guarantee of the full picture of how Haughey acted or thought, it combined with the passage of time, certainly will allow a far more rounded, historically robust account of his legacy.

Writers of political biographies, particularly with a figure like Haughey, either tend to fall into the camps of hagiography or demonisation.

Murphy’s attempt to stay clear of either approach is welcome for those who were not old enough to have met Haughey but who wish to escape the caricature and get an understanding of his true character.

Despite a number of early rejections at elections, once in the Dáil from 1957, Haughey displayed a cunning and ruthlessness that helped him rise through the ranks at a rapid pace.

Serving as minister for agriculture, justice, health and social welfare and finance under his father-in-law Sean Lemass and then Jack Lynch, Haughey was seen as a most able minister.

Most of the civil servants who worked with him in his early ministries found him to be “head and shoulders” above others that they had worked for.

Top justice official Peter Berry considered Haughey the best of the 14 ministers for justice that he served, even though he was highly critical of him from an ethical standpoint, as Lenihan pointed out in his 2016 book.

Haughey was responsible for the Succession Act, which was a monumental piece of legislation. Opponents including the Fine Gael leader James Dillon described him as a “brilliant minister”. But there was a darker side.

He developed a reputation that when the pressure was on, he was prepared to blame anybody, shaft even the closest of allies, and he betrayed everyone.

The 1970 Arms Crisis and subsequent trial was probably the lowest of low points in Haughey’s career, which ultimately left him in the political wilderness for several years.

During the trial, he abandoned his co-defendants and pretended he really did not know what was actually happening in relation to the importation of arms to aid northern nationalists.

Of course, he knew what was happening, and as UCD historian Diarmuid Ferriter concluded: “Haughey in the witness box lied through his teeth.”

But if Haughey knew what went on, it is also clear so did his Taoiseach Jack Lynch.

In delivering his summation of evidence to the jury, the judge remarked that they had to believe either Haughey or defence minister Jim Gibbons and one of them had to be committing perjury.

Ultimately, all four defendants were acquitted on October 23 and Haughey immediately called on “those responsible for the debacle” to consider their position. He clearly meant Lynch, but the party rallied around its leader and the Taoiseach survived.

Despite the acquittals, Haughey was cast to the backbenches but rather than leave Fianna Fáil like Neil Blaney and Kevin Boland, he saw his only route back to power as being in Fianna Fáil.

The bitter divisions within Fianna Fáil which emerged over the Arms Trial would remain for nearly 25 years until Bertie Ahern became leader.

Haughey would eventually be brought back into the Fianna Fáil frontbench by a reluctant Lynch and set his mind to ousting his leader.

He returned to the Cabinet after the 1977 landslide election victory for Lynch and Fianna Fáil and within two years, he saw off George Colley to become the new leader and Taoiseach.

With his mother in the public gallery in the Dáil on the day he assumed office, Haughey endured six hours of vitriol and character assassination from the opposition with Fine Gael leader Garret FitzGerald saying he had a “flawed pedigree” in that one third of his own party felt he was not suitable to be Taoiseach.

The jibe — which “reeked of social snobbery” according to Martin Mansergh — stung the Haughey family which had survived many hard times and the loss of Haughey’s father to MS at the age of just 48.

His first two tenures as Taoiseach were mired in controversy.

Between 1981 and 1982, he lost two elections, and won another only by dint of some curious deals with fringe independents.

His party was shaken by a series of scandals. Of these, perhaps the most notable involved the 1982 case of an impoverished Dublin socialite, Malcolm MacArthur. When he was finally apprehended, after having killed twice, it was on the property of Attorney General Patrick Connolly, with whom he had been staying for some time as a guest.

Haughey famously described the episode as “grotesque, unbelievable, bizarre and unprecedented,” and the acronym GUBU passed into the Irish political lexicon.

Far more serious was the revelations that the Haughey government, through its Justice Minister Sean Doherty had tapped the phones of two journalists.

Having been dumped out of office in 1982, the Fine Gael government did not flinch in publishing the revelations.

Under severe pressure, Haughey came close to resignation but he overcame the scandal as well as reports that he had an overdraft from AIB of more than £1m.

A succession of failed heaves only served to poison the atmosphere within Fianna Fáil even more with his opponents accusing him of operating a reign of terror with TDs being intimidated, followed and their phones bugged.

Read More

One night on the plinth at Leinster House Jim Gibbons was seriously physically assaulted by Haughey supporters leading many to question how stable democracy in Ireland actually was.

From his earliest days in politics, Haughey sought to exist on a level above all other politicians.

The purchase of the period mansion in Kinsealy, later an island off the coast of Kerry and his grooming of himself into a cultured European statesman was largely done either through bank overdraft or donations from wealthy friends.

As stated by his son Sean, scarred by his impoverished childhood, Haughey was determined to enjoy “the good life”.

As Mansergh put it, Haughey belonged to a generation that wanted to escape from frugal living, and to make Ireland a country like America, with lots of wealthy people.

“His mistake was to try and emulate the living style of Ireland’s few really successful entrepreneurs,” he wrote.

“There were huge dangers in his dependence on large private donations, as pointed out in the McCracken Report. Rightly the Oireachtas moved to regulate that whole area. He never anticipated that he would be found out by accident,” Mansergh concluded.

In 2000, the Moriarty Tribunal identified payments totalling €8.5m that appear to have been made to Charles Haughey between the years 1979 and 1996.

The tribunal calculated that Ben Dunne, former Dunnes Stores Executive, gave the former Taoiseach more than £2m.

“Who needs eight million,” exclaimed Bertie Ahern in 2005 when asked about Haughey’s reliance on donations from wealthy benefactors.

It also emerged that of the £270,000 collected in donations for Brian Lenihan’s liver transplant, no more than £70,000 ended up being spent on Lenihan’s medical care.

The tribunal identified one specific donation of £20,000 for Lenihan that was surreptitiously appropriated by Haughey who took steps to conceal this transaction.

We also know that Allied Irish Banks settled a million-pound overdraft with Haughey soon after he became Taoiseach in 1979; the tribunal found that the lenience shown by the bank in this case amounted to an indirect payment by the bank to Haughey.

Aside from his financial improprieties, Charles Haughey faced scandal in his personal life, with the revelation of his long-term affair with the journalist Terry Keane, the wife of a judge he had appointed.

She shared his luxurious lifestyle, and for several years wrote a society column in the Sunday Independent which hinted at the liaison, with references to ‘Sweetie’.

Having been a strong opponent of proposals to remove the prohibition of divorce, Haughey was portrayed as a hypocrite.

He certainly enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, with luxury foreign holidays, expensive meals and fine wine. He wore shirts bought for £700 each in Paris.

His decision to sack his great friend and tánaiste Brian Lenihan senior during the 1990 presidential election at the behest of O’Malley and the PDs ultimately sparked the end for Haughey.

By choosing to jettison his greatest ally in order to remain in office he revealed to his thirst for power, no matter what the cost.

He eventually bowed to pressure in 1992 when Sean Doherty revealed that Haughey had known all along about the tapping of the phone of journalists back in 1981, thus ending the career of the single most dominant politician of his generation.

Any fair and objective analysis of his life in politics will have to recognise Haughey’s career had genuine highlights with many of his initiatives having a lasting positive legacy.

As minister for finance during the late 1960s Haughey introduced free travel for the elderly.

In 1972, while in the political wilderness back home following the Arms Trial, Haughey was invited to speak at Harvard about his ground-breaking artist’s tax exemption scheme which he described as was an attempt to halt the intellectual drain of Ireland’s most creative people leaving the country. Many credit Ireland’s genuinely world-class equestrian industry to the various tax breaks he introduced while in Finance.

He backed the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC), which now employs many thousands more people than originally envisaged.

He backed Temple Bar which is a major attraction for international tourists and he supported Knock Airport against the “metropolitan knockers”.

By the time Haughey retired, Ireland, with the help of social partnership and EU Structural Funds — both of which he helped negotiate — was on a path towards parity with average EU living standards, and the peace process was beginning to take shape in the undergrowth.

Prof. Murphy’s book, which will be reviewed in the Irish Examiner next Saturday by another former Taoiseach John Bruton, is a well-timed reflection on the most historically interesting figure in Irish politics since de Valera.

The caricature of Haughey that haunts the established history of late 20th century Ireland is one of a greed-driven, venal, ruthless figure who sacrificed all in the pursuit of power.

Such a picture is only partly true. The reality is far more complex and nuanced and it is high time those complexities are explored.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates