Terry Prone: How the truth can change the lens in which we view an entire life

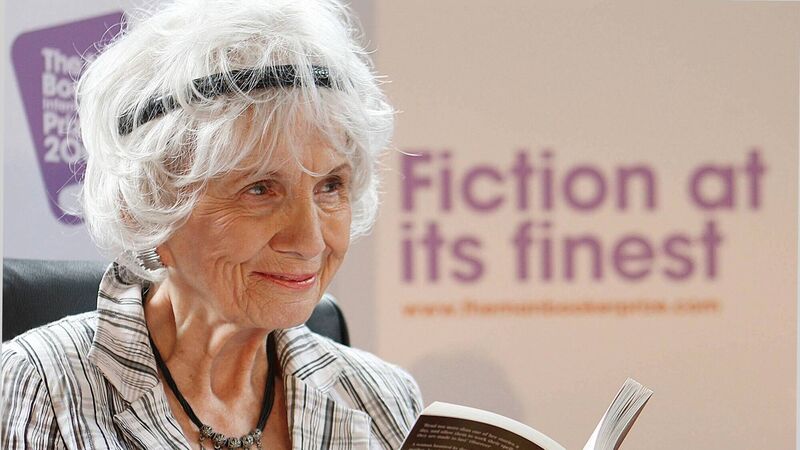

Alice Munro’s literary legacy will always be influenced by her family secrets and protection of her daughter’s abuser

Her second husband sexually assaulted her nine-year-old daughter. Many times. This is not in dispute. He did it and later confessed to doing it.