Sarah Harte: Do new Irish citizens need to know more about what it means to be Irish?

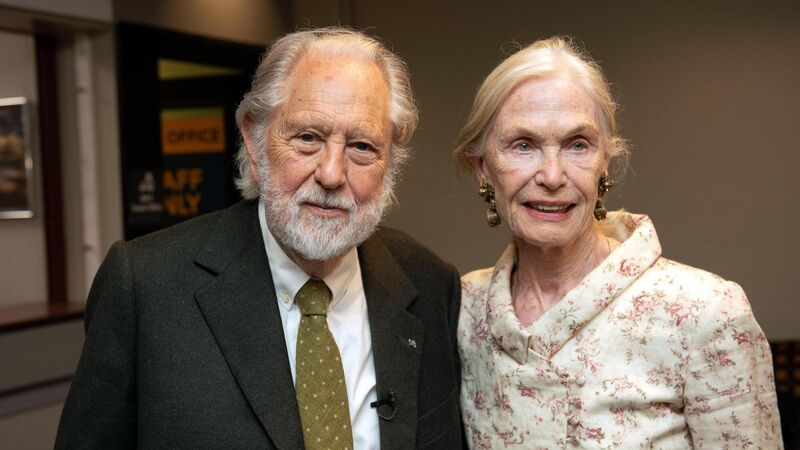

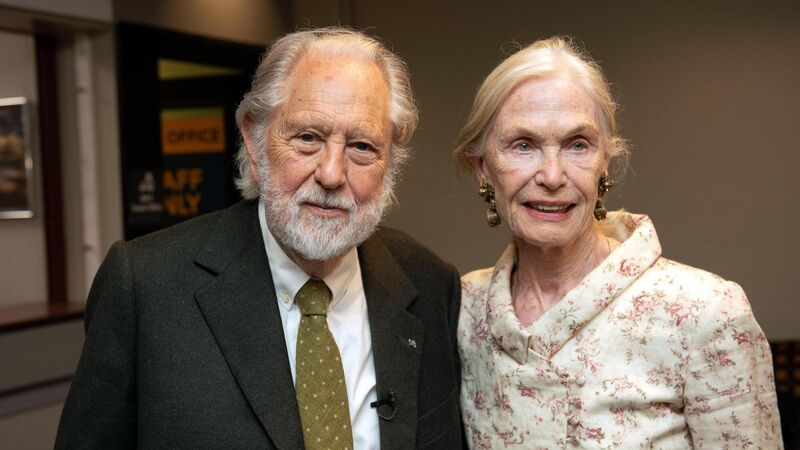

David Puttnam after receiving his Irish Citizenship along with his wife Patsy in Killarney. Picture: Sally MacMonagle

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

David Puttnam after receiving his Irish Citizenship along with his wife Patsy in Killarney. Picture: Sally MacMonagle

When words like ‘crackdown’ and ‘fester’ are hanging in the ether, it’s hard not to feel depressed. At least our public discourse hasn’t been degraded to the extent that senior politicians feel able to compare migrants, as former American president and card-carrying idiot Donald Trump did at the weekend, to Hannibal Lecter, claiming that they’re all escaping from ‘insane asylums’.

But it was a relief last Friday to hear Public Expenditure and Reform Minister Paschal Donohoe, say that we should not lose sight of the positives of openness and people coming here.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Select your favourite newsletters and get the best of Irish Examiner delivered to your inbox

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 5:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited