Clodagh Finn: The ‘Irish matchgirl’ who helped to change history

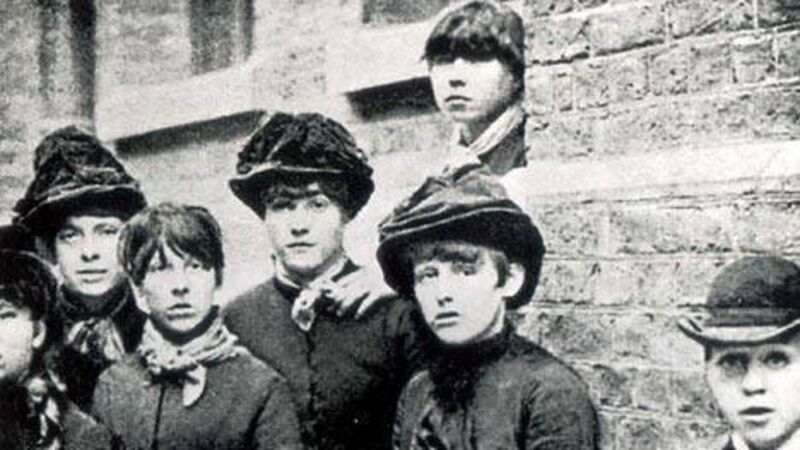

‘Matchgirl’ strikers, several showing early symptoms of phossy jaw, a form of bone cancer that affects the jaw, teeth, gum and face. It can also lead to brain damage.

The name Mary Driscoll might not ring a bell but this woman, considered the “lowest of the low” in her society, was just 14 years old when she became one of the leaders of a strike among match-factory employees that helped improve working conditions for everyone.