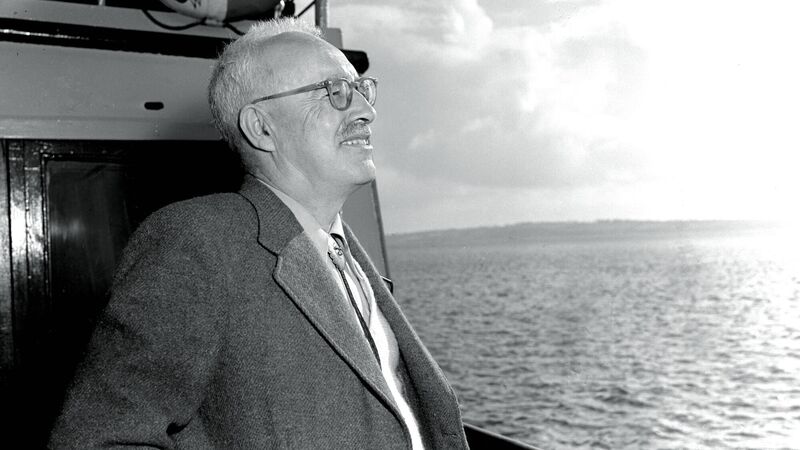

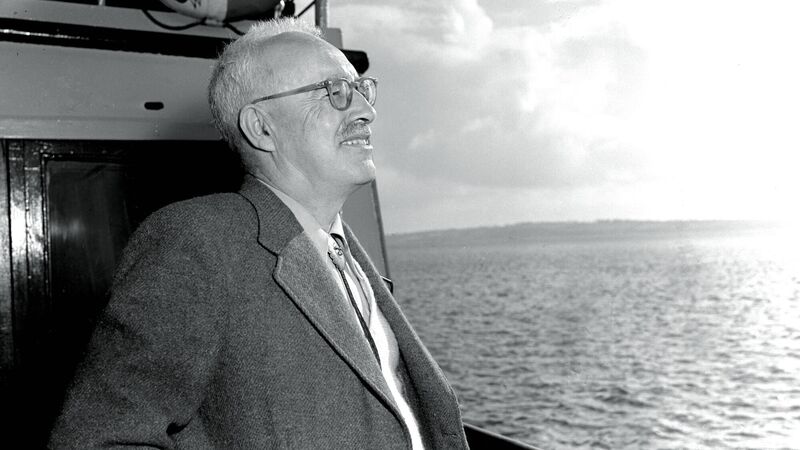

Michael Moynihan: Frank O’Connor’s book cover images show Cork life through a lens

Cork author Frank O'Connor. His stories about the Cork he grew up in are often claustrophobic, with all the petty snobberies born of narrow streets,

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Cork author Frank O'Connor. His stories about the Cork he grew up in are often claustrophobic, with all the petty snobberies born of narrow streets,

I've mentioned the famous clip of Frank O’Connor and Huw Wheldon here before, and most readers are surely aware of it by now. The footage comes from the BBC show Monitor which was shot in Cork back in 1961, and in the clip O’Connor talks about the city’s influence on him, and its general significance.

“You don’t have to sell Cork to me, Huw,” he says to the interviewer. “After all, to me it’s the most important city in the world.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Select your favourite newsletters and get the best of Irish Examiner delivered to your inbox

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 9:00 PM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 12:00 PM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 8:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited