Terry Prone: Martin and Kenny are examples of honest and decent politicians

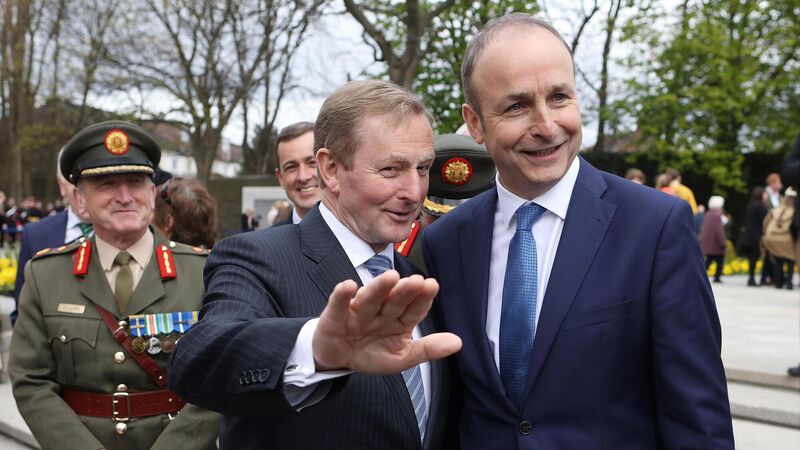

Enda Kenny with Micheál Martin at Arbour Hill in Dublin. Commonsense and the capacity to find joy in every working day are the eternal verities of good politics.

Taking the train to Cork a few weeks ago, juggling ticket, briefcase, coffee and coat, I sent a prayer of gratitude up to nobody in particular when the ticket travelled through the machine in proper order and up went the barrier.

In normal circumstances, no more obstructions could be expected on the way to the platform where the train for Kent Station awaited. Normal circumstances, however, didn’t apply. Instead, a considerable traffic jam had built directly after the ticket checking area. Hundreds of people locked solid, nobody moving. Well, that’s not quite true. Up ahead in the crowd were phones being raised overhead to take pictures of people who were taking selfies of themselves with some celebrity or other. As the group around the celeb shifted, it was possible to see the back of his head. Blond hair and plenty of it, substantially greyed. Not saying I know the back of his head that well, but I was pretty sure it belonged to Enda Kenny, former Taoiseach, former leader of Fine Gael, former TD.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Subscribe to access all of the Irish Examiner.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates