Clodagh Finn: Ireland of 1986 felt like an unforgiving, inflexible place for a young female student

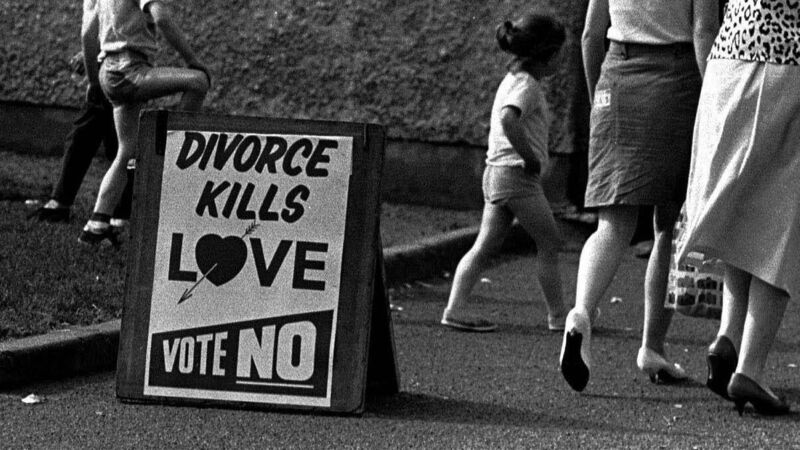

Polling Day in Ballymun for the dicorce referendum. The resounding no vote left those suffering marital breakdown, estimated at about 80,000, in 'the most horrific hiatus.' File picture:

When I think of 1986, the memory that pops to the surface is the burning tang of the three-bar electric heater and the circle of heat it threw out into my Dublin 6 bedsit. I can also vividly recall the shock of inhospitable cold that smacked you hard if you happened to put a toe outside that cosy, artificial sphere.

It was like that in the outside world too.

In the warm circle of friends and fellow journalism students, it was an exciting time to be alive. We were learning how to chart the world, if not yet dare to try to change it. Change, as we had seen only too forcefully, seemed nigh impossible.

That was hammered home in the empathetic defeat of the divorce referendum of June 26 when the country voted by 63% to 37% to keep the constitutional ban in place.

From this remove, it’s interesting — and rather heartening — to look back on the coverage and see that the reality of marital breakdown was to the forefront during the shrill campaign, and afterwards.

The resounding no vote left those suffering marital breakdown, estimated at about 80,000, in “the most horrific hiatus”, this newspaper’s editorial writer said the day after the vote. And the paper left readers in no doubt about what must happen next: “Those who worked so selflessly to defeat the referendum now have an equal duty to succour those victims of broken marriages who require a legal alternative.”

If there was compassion in those lines, it didn’t seem to register on the ground. The Ireland of 1986 felt like a very unforgiving and inflexible place for a young, female student.

Part of that was down to the divisive divorce campaign. The slogans are recalled now with a mixture of disbelief and amusement. They may have lacked the punch of the famous 1995 divorce referendum slogan “Hello divorce, goodbye Daddy” but they still exploited unfounded fears that a stampede of men would exit their marriages if divorce was legalised. (The moral crusaders didn’t have much faith in men).

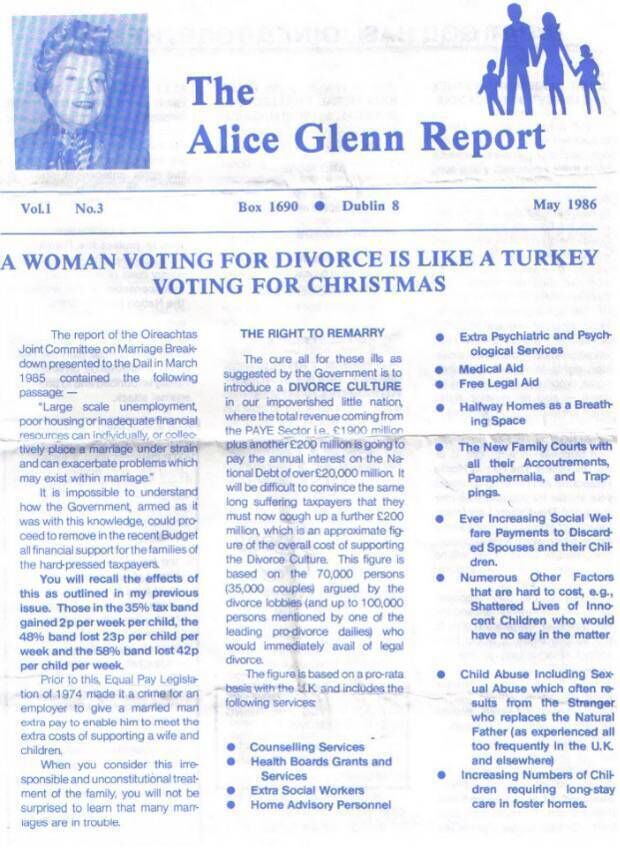

The standout line for me, though, came from the inimitable Fine Gael TD Alice Glenn, who went against her own party to tell us that a woman voting for divorce was like a turkey voting for Christmas.

It was masterful because, as well as being memorable, it highlighted the very real lack of family law legislation to deal with property and children’s rights post-divorce.

There was another line, too, trotted out in the heat of debate which seemed to reflect a fairly widespread belief that marriage, even a bad or a violent one, was for life. It went: “She’s made her bed, now she’ll have to lie in it.” The harsh inflexibility of that still makes me bridle.

I never heard it said in relation to men but maybe that was because there was still no public consciousness that men could also be victims of domestic violence. So much was still hidden.

It was not really a surprise when the referendum was defeated that June, although some of the statistics surprise me now. A vehement 79% voted against it in Cork North West, while the figures in Cork City (66%) were much closer to the national average of 63%. (Carrigaline was alone in city and county in voting for divorce).

What was most unnerving about the outcome, though, was not just the turning of a blind eye to the reality of marital breakdown; it was more how closely the results mirrored the so-called ‘pro-life’ referendum of three years before, when 67% of Irish people voted to insert the controversial eighth amendment into the Constitution.

Even as a 16-year-old, I could see that equating the life of the mother with that of her unborn child was an admirable ideal but unworkable; there would be situations when you’d have to make a choice. We were told by the people who wore tiny little feet on their lapels that was never going to happen.

We know differently now, of course, but in 1986 what struck me most as a young woman was the hypocrisy of a country that valued unborn life so much but had such scant regard for those perfect little feet once they arrived on this earth.

Or more accurately, when those perfect little feet were born to women who were not married. If you stepped outside the norms in the Ireland of 1986, you fell off a cliff. Or that is how it seemed to me in bedsit-land where unmarried mothers, as we called them then, were trying to survive on an allowance of £54.40 a week.

There’s nothing new in the financial struggle faced by single parents. In 2025, almost half of all one-parent families lived in enforced deprivation (46.3%), compared to 16.2% of two-parent families, according to recent One Family statistics.

Some 40 years ago, though, single women were condemned not only to poverty but to public disapproval.

You’ll find a particularly revealing insight into those attitudes in a clip from Gay Byrne’s radio show from the RTÉ Archives of 1986. The title says it all: “These girls are getting away with something.” In it, Byrne asks why taxpayers should support unmarried mothers at a time when so many married mothers are also struggling.

“There is a feeling,” he says, “that these girls are getting away with something — promiscuity, rampant in our society — and they are being paid to do it.”

To be fair, he was being slightly tongue-in-cheek, and the discussion continued with more nuance, although he was not wrong about

that feeling.

It was one that filtered down into the consciousness of so many young women and registered as fear. Fear of having a female body. Or a sexual impulse. Or of being in a relationship and going “too far” — a phrase current then.

Living in this country felt oppressive, dangerous even. If you put a step out of line, you might be cast out or condemned to a life of hardship and disgrace.

It was also a time of high emigration and high unemployment. Passing from the general to the particular, the disappearance of schoolboy Philip Cairns in October of that year left a huge mark. His mother Alice died last November without ever finding out what happened to her 13-year-old son.

It wasn’t all bad, of course. In the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (reform) and the winds of change were starting to blow here too.

I discovered theatre and the raw, explosive daring of playwright Tom MacIntyre on the Abbey stage. He was original, bold, and entirely unafraid of pushing boundaries.

There was shelter from society’s cold spots in friendships too and in the very many chats that took place in bars around the city (apart from Bewley’s and the Kylemore, café culture was still a way off). Furstenberg lager had just been launched and a young woman could order a big smooth, honeyed pint of it without raising an eyebrow in most of the capital’s pubs.

It wasn’t enough though. During one of those pub chats, a friend and I decided to leave Ireland, along with some 30,000 other Irish people who emigrated that year for a variety of reasons.

I don’t know how many of them, like me, were just looking for a place where it was a little bit easier to be young and female. Or how many of them, like me, returned home. I did so in 1990 after Mary Robinson was elected president. She gave me hope that the sunless days of 1986 could finally be relegated to the past.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates