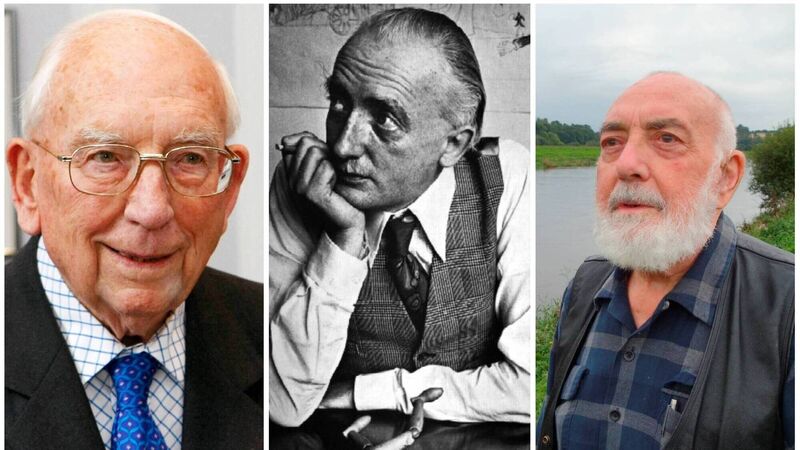

Fergus Finlay: Men of wisdom and character who changed development of Ireland

Economist TK Whitaker, composer Sean Ó Ríada, and poet Thomas Kinsella all had a significant impact on the second Irish revival.

I listened to Greta Thunberg being interviewed by Brendan O’Connor on Sunday, and two words stood out for me. Wisdom and character.

This is a young woman who has taken endless abuse over the years. She has been the subject of intense and detailed lobbying and misrepresentation because her ideas are dangerous to some very powerful vested interests. And she has been utterly steadfast.

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB