Clodagh Finn: Let me show you why Ireland's Heritage Week is my favourite week of the year

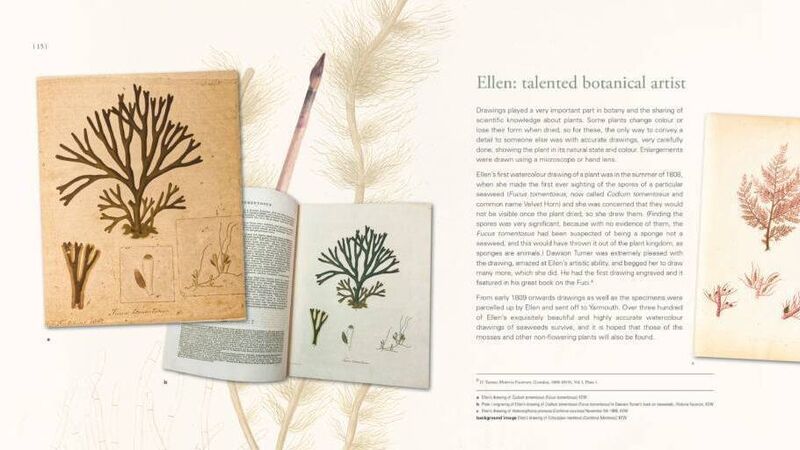

Original drawings by the groundbreaking botanist Ellen Hutchins are beautifully presented in the book by her great, great, grand-niece, Madeline Hutchins.

When I think of Ellen Hutchins, Ireland’s first female botanist and the focus of a festival during this year’s Heritage Week, I always wonder how she felt when she made that bone-jolting journey home in the early 1800s.

Her niece, Alicia Maria Hutchins, described it in such evocative detail that the image of men filling boggy potholes with furze branches and stones so the carriage could continue on its long journey from Dublin to West Cork stayed with me.