Joyce Fegan: David Beckham, as dad, leads by example

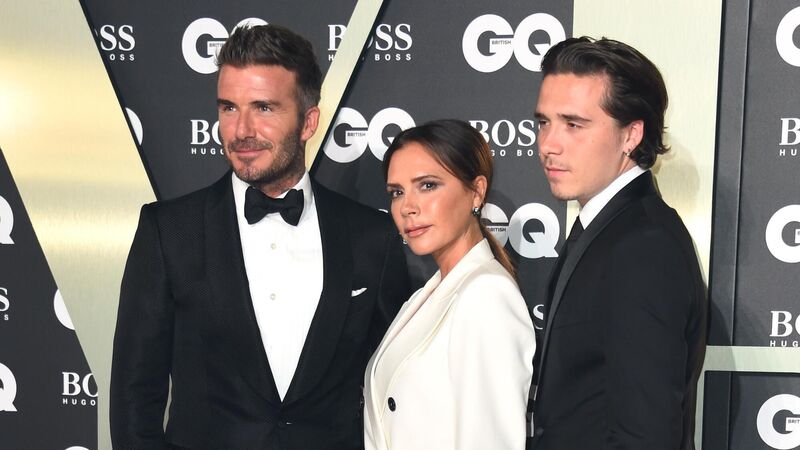

David Beckham, Victoria Beckham and Brooklyn Beckham. The ex-footballer says he tries to control his children's use of social media.

I got a watch this week, a Casio, €22.99. It can't monitor my heart rate and it doesn't know how many steps I've taken in a day. It also doesn't alert me to an incoming call or a message. But it does its job, it tells me the time — one of the main jobs I'd outsourced to my phone.

Smartphones are now our fifth limb. The extent to which they have infiltrated our lives is endless. They're our bank tellers, our navigation systems, our clocks, calendars, cameras and calculators, our recipe books, our shops and checkouts, our source of news, our entertainment systems, our encyclopedias, our at-home valley of the squinting out the windows as we get to observe the intimate lives of others on the various social media platforms and our communication cords for everything from message sending to social life organisation, and from family forums to neighbourhood watch groups.