Terry Prone: Words matter, and Volodymyr Zelenskyy knows their value

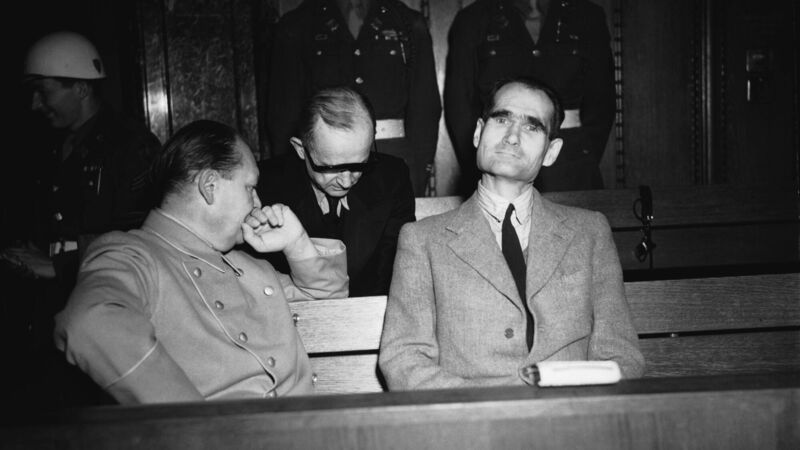

The term genocide was coined by lawyer Raphael Lemkin who battled to have the term included in the indictments at Nuremberg of Hermann Goering (left), Rudolf Hess, and other leading Nazis. Picture: Chris Ware/Keystone/Hulton/Getty

What isn’t grand is the word used in the minutes of a recent board meeting: “The Board expressed grave concern in relation to the incidents, deeming them as unacceptable”.