Maeve Higgins: Colonialism continues to impact climate change

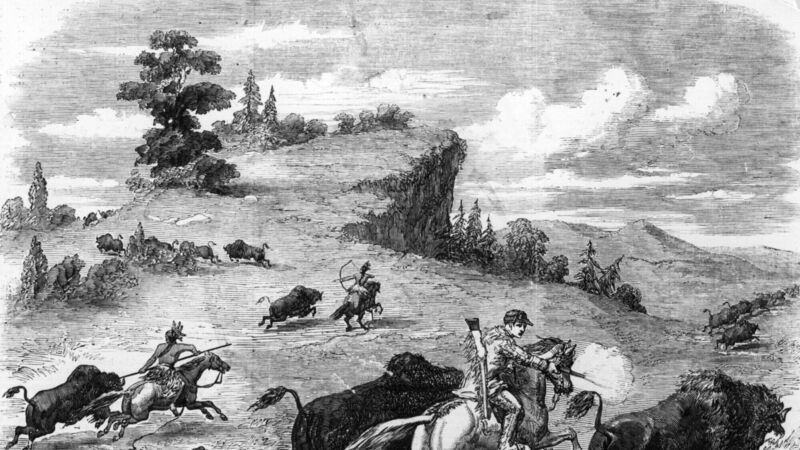

Hunting buffalo by spear, bow, and pistol, around 1880. 'The actual saying from the US army was kill the buffalo, kill the Indian. Buffalo were a vital species to the ecological balance.' Picture: Hulton Archive/Getty