Clodagh Finn: ‘Thanks, Penneys’ best.’ Phrase that dressed a nation has to change

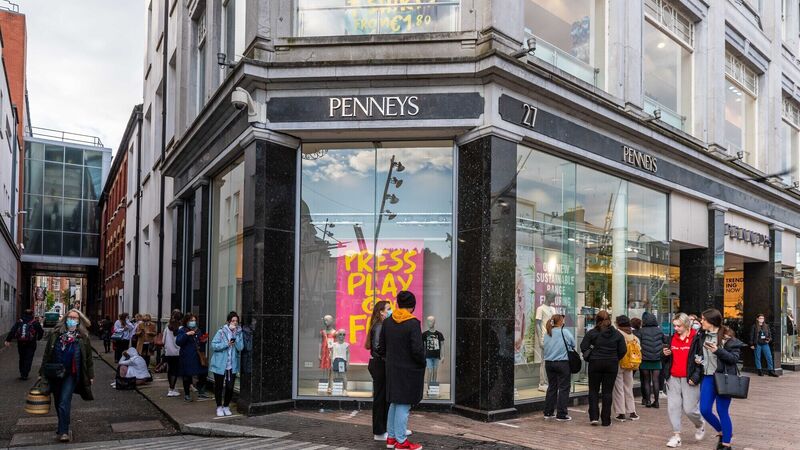

Recall the queues when Penneys reopened, post-lockdown. One wag said they were visible from the moon. Picture: Andy Gibson

As recently as last Saturday, I admired a woman’s dress and she said: “Thanks, Penneys’ best.”

Then she did that thing we Irish women do when complimented; she looked down, plucked gently at what she was wearing, as if to say “this old thing” before shrugging off the attention.

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB