Daniel McConnell: A judgment that may not be in the public interest

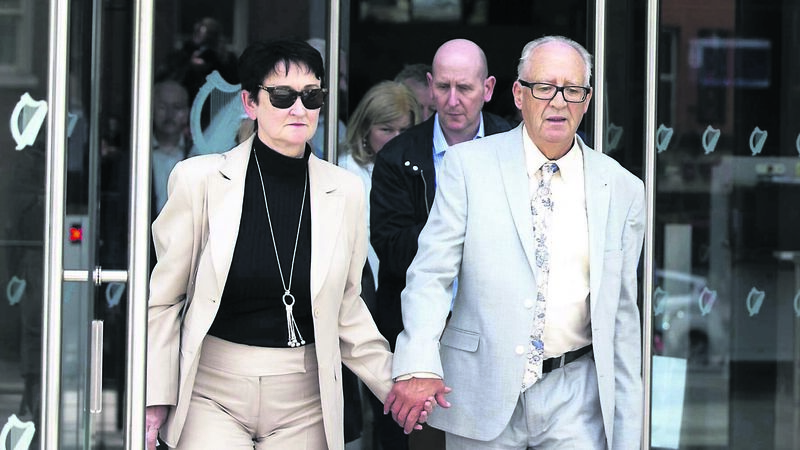

Ana Kriegel’s parents Geraldine and Patrick Kriegel leaving the Criminal Courts of Justice Dublin after the Ana Kriegel Trial finished. Boy A and Boy were found guilty of Ana’s murder. A ruling in the Court of Appeal on Thursday means had that case happened now, the public would never have heard a word of it. Picture: Sam Boal/RollingNews.ie