Michael Moynihan: Back on track - Be wary when Cork light rail system talk comes around

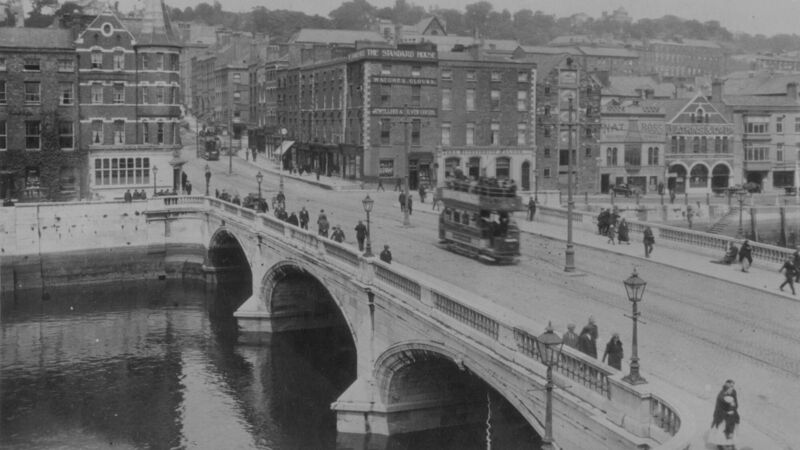

A tram crosses the bridge in Cork City in 1930. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

During the week a pal forwarded a clip of film showing Cork from over a century ago, a clip focusing on one particular part of the city and one particular activity.

You may have seen it — silent images which show an old tram rattling noiselessly along MacCurtain Street, when it was still King Street (and going the wrong way, traffic nerds) before it makes a sharp turn down Bridge Street and the vista of Patrick Street opens up. You can’t help urging the cameraperson to pan left to show us Merchant’s Quay, but it’s straight ahead all the way.