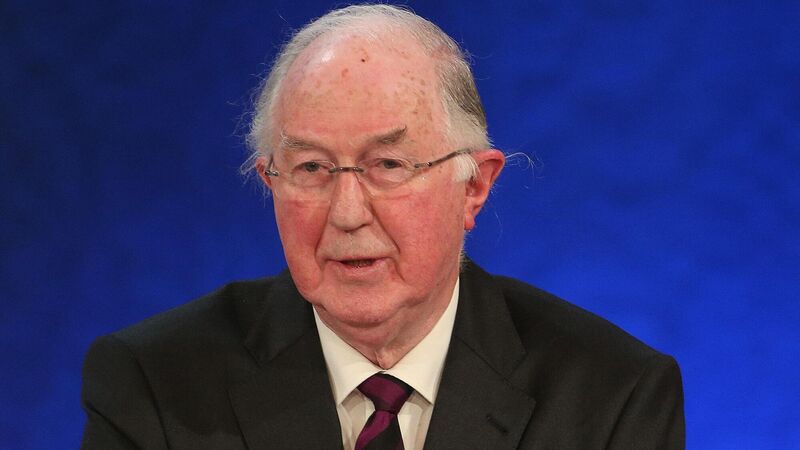

Fergus Finlay: Two men who made their mark on this country and will be missed

I was in a radio studio on Sunday, with two young journalists. Both very bright. Both clued into how politics works and doesn’t work, and both, despite their youth, very savvy about media.

We were discussing the Sunday Independent’s acknowledgement last weekend of the way it had treated John Hume in the period before the major breakthrough in the peace process.