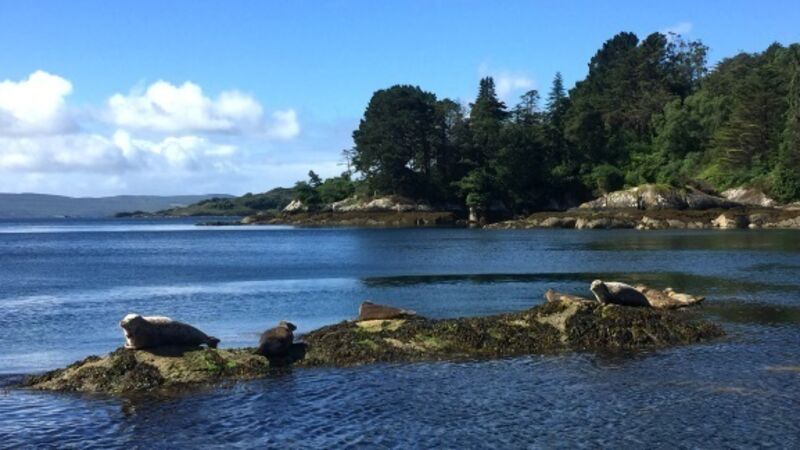

Giving seals a second chance

At the start of a new year, one’s thoughts turn to time. As we age, years appear to pass as quickly as weeks did when we were children.

If your watch has a ‘second’ hand, try memorising how long a minute seems. Then, without looking at the watch, estimate the passage of another minute. Resist the temptation to listen to your heartbeat or count seconds in your head. According to a paper in Animal Cognition, seals can measure short intervals more accurately than we can and they don’t need a Rolex to do so.