No country for old men... or any rural person for that matter

Such were the complaints voiced by outdoor people, convened indoors at the pub last Saturday evening, farmers, fishermen and their wives. The situation, they say, is getting beyond a joke, and Michael Healy Ray is the only hope, and his brother, Danny, behind him.

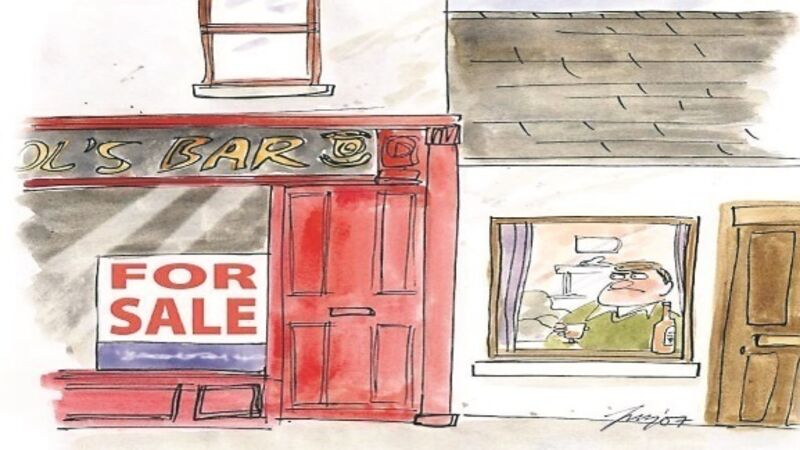

Even where the churches are still attended, many folk from isolated farms, where the only company is cows, sorely miss the news purveyed at the local shop and the pub. This is ‘community’.