Utopian glow off Sinn Féin will fade once they get closer to power

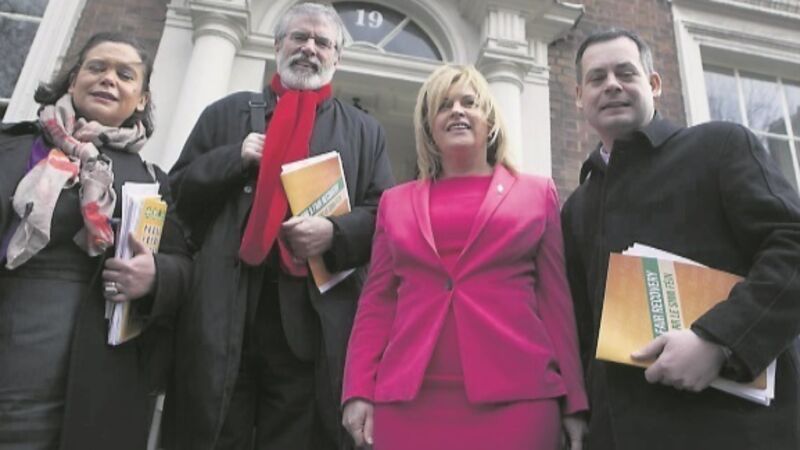

YESTERDAY the Sinn Féin manifesto was published. Freeze frame the picture from Monday night’s debate between the finance spokesmen of the four main parties on RTÉ’s Claire Byrne Live. It is not just that with Sinn Féin’s arrival there is another chair on stage, the dynamic has changed too.

It tightens the space within the conversation Labour has left to manoeuvre in. Not only had the other three a little less time, thematically Labour was squeezed between being in government on the one hand and Sinn Féin being free to roam on its left, on the other.