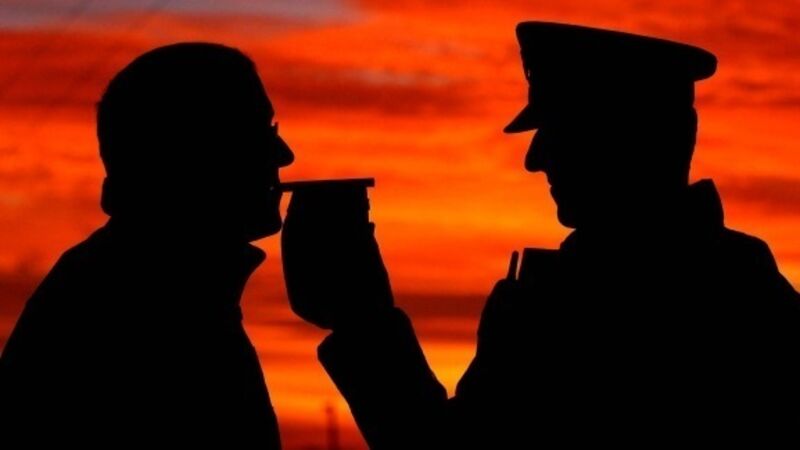

No blowback from breathalyser scandal

Travelling home from a relative’s house one night last Christmas, I was stopped at a garda checkpoint.

The courteous officer looked in on me. “Where are you off to,” he asked, as if I was a wayward teenager and he was my dad.