Whiddy Island disaster: After 45 years families might finally get answers and justice

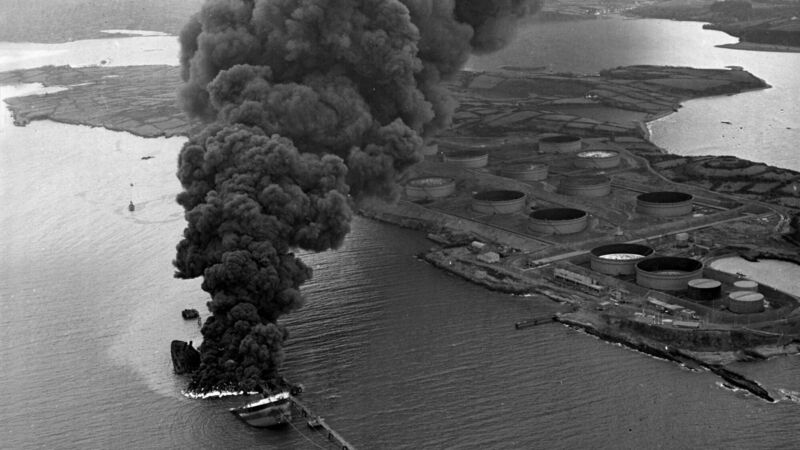

The explosion and resulting fireball from the Betelgeuse oil tanker killed 50 people, both on the ship and on the nearby Gulf Oil jetty. Picture: Richard Mills/Irish Examiner

The son of a victim of the Whiddy Island disaster says he is prepared “to go to the well of his being time and time again” to get justice for the victims’ families.

International maritime law expert, Michael Kingston, was speaking ahead of today's 45th anniversary of the devastating maritime tragedy that claimed the lives of 50 people, including his father, Tim, leaving their families shattered, and casting a long shadow of loss and pain over the region for decades.