Occupied France offers literary response

In May 1915, the war that was to end by the previous Christmas was still raging.

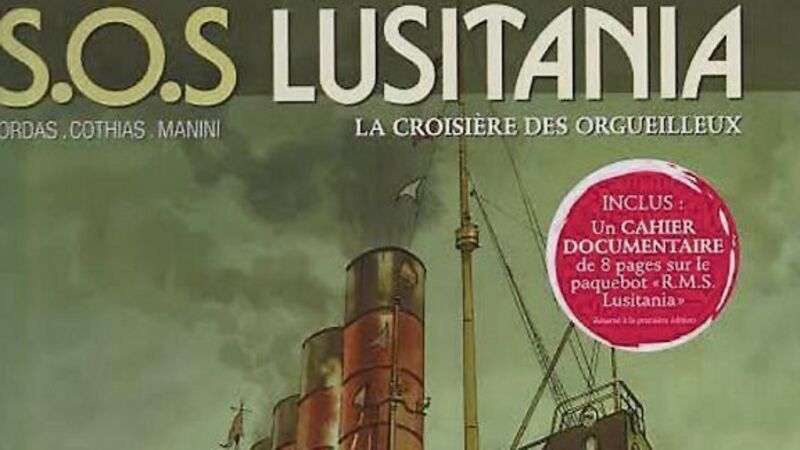

Then, on May 7, a speedy resolution to the conflict looked further away than ever when news broke of the sinking of the Lusitania off the Irish coast.